|

| Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, 2020 Detail |

Damien Hirst's Cherry Blossoms are like nothing else shown at the Fondation Cartier in recent years. Likewise, the Cherry Blossom paintings are, at first glance, unlike much of what Hirst has produced over the past decades. This is apparently his first institutional exhibition in France, and that makes the exhibition even more unusual. One would expect to see sharks in formaldehyde, dots and diamond studded skulls in his inaugural exhibition. And yet, the lush, delightful oil paintings seem to find their perfect home in an exhibition set inside the glass house of Jean Nouvel's dynamic building, itself in the lush gardens of the Fondation Cartier. With the light streaming in at the end of the day, glinting on the surface of paint and making the colours sparkle, it's difficult to imagine the Cherry Blossoms anywhere else.

|

| Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, 2020 Installation @ Fondation Cartier |

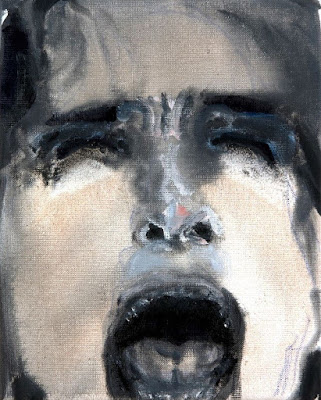

While these luscious and sensuous paintings are quite different from anything we have seen Hirst make over the years, there are obvious similarities to the visual candy and the dot paintings. If the dot paintings are about control and systematization of colour, the uniformity of the application of paint, the formal geometicality of the canvas, the cherry blossom paintings are the very opposite. Thick globules of paint are lovingly applied with fingers, sticks, and brushes, left to coagulate and blister unpredictably over time. The intensity of paint still in the process of drying mimics the ephemerality of the blossoms that will, eventually, wither. And yet, in this, they continue the artist's career-long preoccupation with death, the body, the disintegration that comes with the passing of time — in a dead animal, a promise of renewal in medicine cabinet.

|

| Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, 2020 Detail |

Up close to the paintings, I was reminded me of Cy Twombly's mid-career works in which congealed paint sometimes falling off or moving around the canvas makes visible the presence of the artist's body that was once there. The difference, however, from Twombly's paintings is that the traces of him on the canvas are revellations of the artist thinking, even in the doodlings. Hirst's blobs and globules of paint are intensely physical and emotional. They are the manifestation of an artist at one with the canvas, delighting in the possibilities of his medium. Unlike much of Hirst's other work from the past 35 years, they are the work of a painter playing in his studio, alone with his paints. On these brilliant canvases, we see Hirst free from the demands of the structures, grids, formal principles that overwhelm his work of the past thirty years. It is as though he lets go of all the pressures of being an artist from whom the world has expectations.

|

| Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, 2020 Installation @ Fondation Cartier |

It is also refreshing to see how non-masculine these paintings are. They may be huge in size, and placed side by side in his studio, forming one enormous frieze of cherry blossom trees, but they are not big powerful works expressing an overblown male ego. This is not to say that these canvases are delicate, but they are ephemeral. It is as though they capture the lightness of air blowing blossom from the trees and swirling in the air. There is no control to the blobs and daubs, but rather, they appear, like a rainbow in the sky. Indeed, the arbitrariness of their application gives them movement as they blow in the wind.

|

| Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, 2020 Detail |

|

| Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, 2020 Detail |

I overheard one of the guides saying that because the paint is so thick, much of it has still not yet dried. And when it does, the colours will change, they will become dull, like the falling of blossom from the trees as the seasons move from one to the next. The transience of Hirst's paint, the abstraction of the compositions, and the sensuous joy that we experience in their presence fills them with surprise and joy. But, let's not forget, these works are also pervaded by the promise of death. After the sun has stopped shining over fluttering blossom, the only thing for them to do is to die.