|

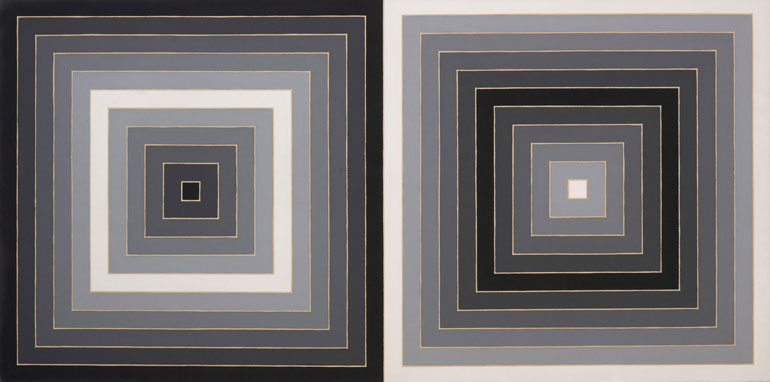

| Frank Stella, Untitled, 1965 |

I had the privilege of giving the lunchtime lecture at the

beautiful Art Gallery of New South Wales last week. And for those who missed it,

I talked about one grey painting, Frank Stella’s abstract work, Untitled from 1965. Even though Stella’s

impetus was to find a form of abstract art that would remove it from all

reference to art history and to the world in which it was produced, the

historian in me couldn’t resist starting off by thinking about what was happening

in 1965 in the United States. The country was falling further and further into

the chaos of the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King led the civil rights march

from Selma to Montgomery in a push to bring voting rights to the fore, while the

space race and the cold war were bubbling away in the background. Given the repetition

of parallel lines in the form of a square on Stella’s canvas, at first glance, it

looked as though he was successful in his plight to remove painting from all

reference to the world.

However, as critics over the years have noted, these

pre-Minimalist works are not without trace of their creation. Stella left his

mark, not only in the form of grey parallel lines, but in what might be seen as

the most vulnerable place on the canvas: the slither of canvas left blank in

between the bands. While the width of the bands is determined by the size of

the stretcher bar, thus removing decisions and personal motivations of the artist,

he did not paint the bands with the use of masking tape. Up close, the wavering

line of the artist’s brush moving down the pencil-drawn edges reveals the human

hand, thus the fallibility, that has created the image. In addition, those

spaces, however slight, allow for the possibility of chance, unpredictability

and ambiguity.

Standing back from Untitled

from 1965, we recognize that the thin line of canvas left blank is key to the movement

and pulsating energy of the canvas, as well as the dynamic play of our eye as

it moves in and out of the receding tunnel created by the greys. The blank

space—that Stella has likened to the space between the cars of the New York

subway—both connects and separates the receding shades of grey. The space where

no paint appears, the uneven sides of which are defined by the movement of the

artist’s hand, are in fact the most critical spaces on this canvas. And when we

bring the bands to life as we attempt to capture the entirety of the painting

in a single look (the impossibility of which ensures we stay before the canvas

trying nevertheless) a reference to the world outside of the bands emerges. These

challenges to perception and our constantly altering vision in front of Untitled (1965) gives it a

dimensionality that both reinforces and undermines the purity of its

abstraction.

In 1964, Stella famously declared of his paintings: “What

you see is what you see.” By championing purely formal concerns, he was

ostensibly reacting against the rhetoric of subjectivity and romanticism with

which abstract expressionism had been charged. However, the vibrations of the grey

house paint, their subtle unevenness, and the spatial transformations generated

by the patterning produces an optical ambiguity that ultimately gives rise, as

Stella conceded, “to emotional ambiguities.” Today, over fifty years later,

these ambiguities are even more apparent. In a post-Minimalist era when, one

might argue, art has reached the aspirations of Stella’s one time radical

vision, the artist’s intimate relationship with his painting and the possibility

created by the places he chooses not to touch, are sumptuous and filled with

the romanticism for which abstract expressionism was chided.

No comments:

Post a Comment