The shapes and forms in sculptural and painted works remind us of things as variant as vaginas, bleeding wombs, monsters running rampant through volcanic landscapes, fire and rage of mythical proportions. The body and the natural landscape join forces in agony, screaming for help, watching their own disintegration at the hands of an unrelenting force. It's mindboggling to think that this is what Kapoor produced in lockdown, while we were all on Zoom meetings, avoiding people in the supermarket and getting depressed on our sofas.

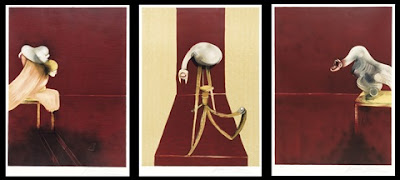

The Lisson gallery flyer mentions Kapoor's engagement with the history of art, reminding us that artists from Leonardo all the way to Francis Bacon have been obsessed with raw flesh and meat. Halfway through the exhibition, it becomes clear that Kapoor is not making vague references to his predecessor's concerns, but rather, that he draws specifically on the work of Francis Bacon, if not others. Kapoor followers will remember the Rijksmuseum's coupling of Kapoor's Internal Object in Three Parts (2013-2015) and Rembrandt's Carcass of an Ox. The artist's debt to Rembrandt is well known. And in the works on view at Lisson Gallery, the debt to Bacon is unmistakeable. Even before seeing the three-dimensional frame in the corners of the untitled works on paper, Bacon's gaping mouths, bleeding wounds, distorted and deformed flesh, screaming with pain are so clearly haunting Kapoor's intense and angry abstract compositions. As much as the triptych Diana Blackened Reddened (2021) might be about fertility and hunting, it is also about Francis Bacon's Second Version Triptych 1944. As Tate's website blurb quotes, Bacon's is a work that reflects "the atrocious world into which we have survived." One gets the feeling that Kapoor's triptych is saying something similar.

|

| Anish Kapoor Installation @ 27 Bell Street, London |

And then, we must not forget that these works are also about painting. Where the raw flesh of a body slaughtered body hangs limp over an unrelenting steel frame, so paint is filled with emotion and rendered alive in the accompanying paintings. But, by extension, paint is as connected to death in these works as Damien Hirst's Cherry Blossoms are to life. It is as though Kapoor were saying something to the effect of painting cannot be separated from flayed bodies, oozing entrails and violently desecrated souls. Painting is about the destruction of our humanness. In turn, if Kapoor is so intent on seeing our bodies slashed and slammed in the abattoir of existence, then he must also be saying something about the modern condition. Certainly, there is not much to look forward to—unless of course, the pleasures of the flesh are also captured in these visceral distortions. Certainly, the proliferation of bleeding orifices and spewing volcanoes would strongly suggest that death and sex are never far apart.

This exhibition is breathtaking from beginning to end.

This exhibition is breathtaking from beginning to end.

No comments:

Post a Comment