|

| Installation view of Anselm Kiefer pour Paul Celan Grand Palais |

It's difficult to know how to put Anselm Kiefer's installation at the Grand Palais' ephemeral space into words. Pour Paul Celan might be inspired by the poetry of the German language writer, but there's something about these works that allows them to exist in a realm above and beyond the mere human world of expression and emotion. Kiefer is attracted to Celan for his creation of a language in the silence and blind spots of language. If Celan speaks what cannot be spoken, writes what cannot be written, in this series of massive works, Kiefer paints something that cannot really be painted. The works are material objects that don't so much represent as give visual and textual articulation in a space where the ability to find form through materials no longer exists. These works are unlike anything that we know art to do.

|

| Anselm Kiefer, Denk dir - die Moorsoldaten, 2019-2020 |

On entering the hangar-like space, visitors step into a dark world, filled with enormous, monumental canvases sitting on moveable bases. I was fascinated by the contradictions immediately thrown up by enormous canvases on wheels—all of the intransigence of the past layered onto their surfaces is undone by the suggested transience of their place in an ephemeral space. This undercutting of the monumentality of his works is, of course, typical of Kiefer's tendency to undo his most definitive claims. Indeed, we find it repeated at every level of every work in the exhibition.

|

| Anselm Kiefer, A la pointe acérée, 2020-21 |

|

|

| Anselm Kiefer, Monh und Gedächtnis/Poppy and Memory, 2020-21 |

In a signature Kiefer installation, a lead plane, still standing, but without windows has become a bed for dead poppies and a shelf for lead books. The significance and symbolism of the work is infinite: a lead plane without windows that might never have flown, covered in books, objects that remind us of a country that burnt its books and its Jewish people. Without books, planes, people, what's left to us is a blindness and an ignorance. We have let go of knowledge that we should never have forgotten. The plane may not be going anywhere, but its presence reminds us of a past that is still with us, recalling all who died on and beyond the battlefields. Remembrance, death, and the promise that it never happen again is everywhere alive in the graveyard that is this exhibition.

|

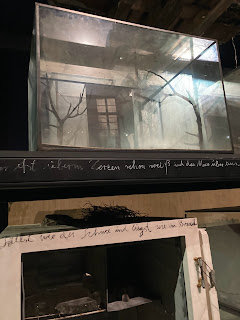

| Anselm Kiefer, Arsenal, 2021 |

In one of the most intriguing installations, shelves of matter and material are displayed as the "arsenal" of the artist. At face value, I assume we are meant to understand the shelves to be filled with Kiefer's ammunition, but the objects are so much more. The structure both reveals Kiefer's tool box and takes the form of an archive of a past that reaches well beyond his own. It is a display and a documentation of the (left over) materials of his artistic practice, comprising many battered objects and desecrated materials that we have seen in earlier sculptures. The objects collected, organized, archived, and sometimes put in drawers range from garden chairs, through the model of a wedding dress, a box of bicycles, shards of glass, ash, dirt, lead sheets, and a wealth of other dusty, dirty ephemera. But the installation is also a materialization of memory, of a past that we have already forgotten, a past that stretches into the depths of the twentieth century. It is a past that belongs to all of us, a past that we have nevertheless deemed no longer useful. On the one hand, we no longer have enough space in our world for the rubble of our material past, for glass shards and dead flowers. On the other hand, for Kiefer, this past is the very substance of who we are.

|

| Anselm Kiefer, Arsenal, 2021 Detail |

|

| Anselm Kiefer, Arsenal, 2021 Detail |

In a world in which the past is so quickly erased by the swipe of a finger, or the closure of a window on a screen, Kiefer's practice is about stuff, about material, about the weight of a past that will not go away. These shelves hold the substance of memory in all its multiple and metaphorical meanings. As my friend Loren said as we stood, looking up at the shelves of broken treasures with the Eiffel Tower twinkling in the background, it is as though Kiefer carted the weight of history from his studio to the Grand Palais. As Loren observed, these monumental installations are so far and above the significance of one person's memory, even of Germany or France. It is as though Kiefer has collected the detritus and reignited the history of human kind. We see the remnants of a world left to decay and disintegrate through the passing of time. In this sense, the installations are of an unimaginable magnitude.

No comments:

Post a Comment