|

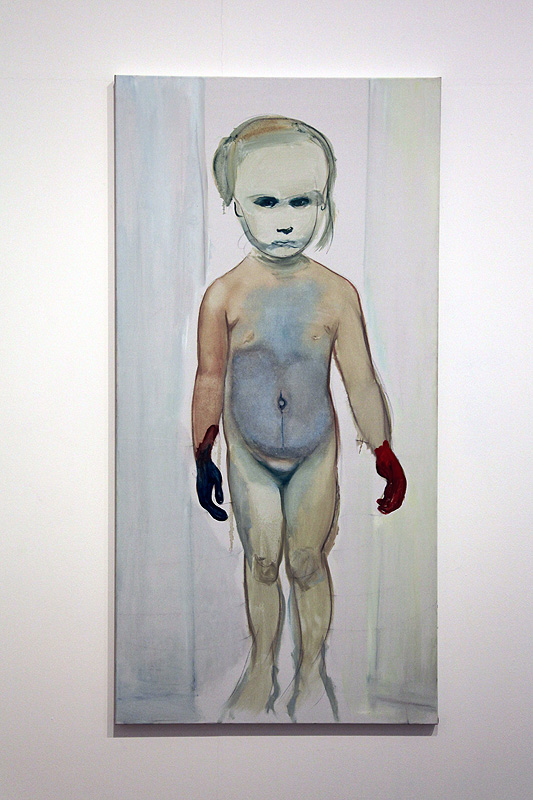

| Marlene Dumas, The Widow, 2013 |

I didn’t know Marlene Dumas’ fascinating

body of work at all. Tate Modern (together with the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam

and the Foundation Beyeler, Basel) have staged a wonderful exhibition of her

work to bring it to long overdue prominence in Europe. The work is politically challenging,

disturbing even, and aesthetically unusual.

The superb exhibition of the works is exemplified

by the space given them – their exhibition in the level four galleries makes

their discovery over time and through reflection possible. To give one example

of why the hanging seems very important to Dumas’ works, the pause between the diptych

in room 14 of two versions of The Widow, 2013

both reveals the narrative of Pauline Lumumba as she is led, bare breasted

through the streets of Léopoldville, surrounded by clothed men, their faces

whited out, following the assassination of her husband by the Katangan

authorities. Simultaneously, the two images are hung side by side to

demonstrate the repetition of a single event: the leading of Pauline Lumumba through

the streets of Léopoldville. And because the second painting is a closeup of

the first, it works as a cut that emphasizes the cinematic form of the narrative

Dumas represents. Across the cut we see an accompanying shift between public

and private experience of Lumumba the wife of the assassinated Prime Minister,

and Lumumba the woman grieving her husband’s death. Such a narrative is

confronting on so many levels: personally, politically, aesthetically.

|

| Marlene Dumas, For Whom the Bell Tolls, 2008 |

Dumas’ work is so unique, that it’s

difficult to know how to approach it. Paintings, poetry, texts, photographs

filled with death, birth, life, violence, advertising and the movies, it

doesn’t look like anything I have in my image memory bank. That said I found

myself wanting to compare Dumas’ work to that of Luc Tuymans. Compositionally,

like Tuymans, Dumas crops faces and bodies, removes the location as context as

well as the mass cultural narrative from which the images are usually drawn.

Her painting like his, comes as a subtle use of cinematic repetitions, edits, closeups,

and spatial configurations. There is no depth to her images, the painting is

fast, superficial. This is what makes them of their time, like his, recognizeably

drawn from mass culture of the photographic age.

|

| Marlene Dumas, The Painter, 1994 |

Unlike Tuymans however, her images are all

about women, and they are about the woman as an emotional, intimate individual

with an interior life. Access to that inner life may be denied, but we

recognize the representation of an individual subject, well before we

understand the public political face she wears. Tuymans’ figures on the other

hand are emotionally distant and placed first in the service of a

cultural/political narrative. Even in the paintings of a series such as the Magdelena we recognize Naomi Campbell,

Princess Diana and Venus, their representation as a discourse on race, class,

fame and fortune, each is more than the painted portrait on which Dumas draws

for inspiration. They are vulnerable, exposed, eroticized, and actively

confronting the desire of their image.

|

| Marlene Dumas, The White Disease, 1985 |

Dumas’ vision of the body is fundamentally

a woman’s vision of the body: women’s bodies are seen, women are violated,

exposed, manipulated, and women confront the eye of the camera. A man could not

have painted these images without being accused of pornographic violation. But

a man would not want to paint these images because they are always in search of

an identity for women, women’s bodies. Even when she paints men's bodies. In the characteristic oscillation

between public and private, the women range from the most highly charged of

all—film stars and porn stars—through the most famous women in the history of

art, to those who should never be seen naked in public: her own daughter. And on her search for the identity of the

woman, Dumas finds death crisis, identity, oppression, the effect of injustice as

it has scarred the human body, the body as painting, the painting as body. These

recurring concerns make Dumas’ body of work frightening. And I kept thinking

that even though she moves to Amsterdam early enough in her life, every time we

turn and look at these women’s bodies, we see the racial injustice and violence

to the men and women of Dumas’ native South Africa.

|

| Marlene Dumas, Magdalena (Out of Eggs, Out of Business), 1995 |

What makes Dumas’ work complex is that it

is always simultaneously about the identity of painting as well as the identity

of women. Dumas questions the status of the female body and at the same time

questions the status of the image. Throughout her body of work she consistently

makes this parallel enquiry but not through easy equation. She achieves the

parallel enquiry through her artistic vocabulary, as well as through the use

of the body in many different kinds of images, by male painters, porn stars,

stripper,s polaroids of her family, highly political imagery. The body is

deformed in and through the use of the watercolour or the paint, use of spray

paint that confuses boundaries, the blackened out eyes that continually

confront the viewer. There is something grotesque in the portrait images of

certain women, there is something grotesque in the repeated desire to represent

the bodies of women in images.

No comments:

Post a Comment