|

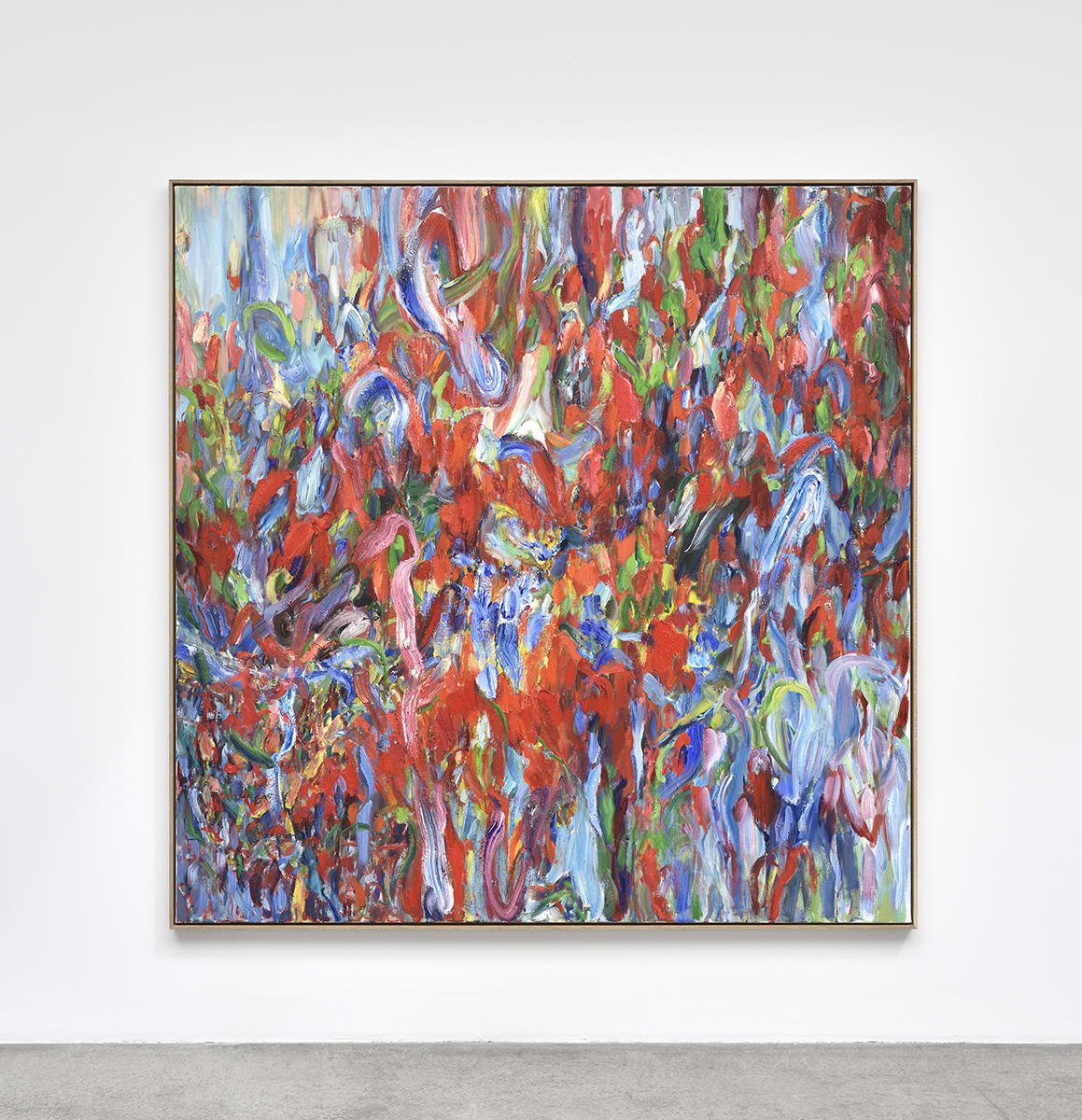

| Sabine Moritz, Night I, 2019 |

As I

perused Sabine Moritz’s abstract paintings on the ground floor of Marian

Goodman, I was strangely unaffected. I was surprised that these colourful,

highly abstract paintings didn’t appeal to me, but I was not convinced they were

doing anything I needed to see or to know about. I have to admit, I was

disappointed to the extent that I wondered if Moritz had established her name

thanks to her famous husband—Gerhard Richter. I know I am meant to look at her work as independent, but it was difficult not to compare it with the

complexity and ambiguity that draws me to Richter’s. Her big abstract

paintings are vivid, rich in colour and paint, moving different shades of the same

colour in different ways around the canvases. However, I didn’t get the sense

that they were doing much more.

|

| Sabine Moritz, Ice, 2019 |

In some of

them, we see flowers exploding, and apparently, they have been realized through

a unique mode of paint application. I was reminded of Berthe Morissot, another painter who was known because

of the men in her life, and indeed, there were moments where I thought Moritz’s

paintings resembled blown up details of Morissot’s. Eruptions of colour with

large (as opposed to short) expressive brushstrokes were resonant of Morissot’s impressionist creations.

However, Moritz’s paintings are flat, superficial, not capturing a complexity

of perspective, depth and creating intimacy with their spectator. Indeed, the

absence of tension was my problem with Moritz’s paintings.

|

| Sabine Moritz, Sea King 82, 2017 |

I found the

figurative works in the downstairs gallery to be more interesting. The four

walls were covered in helicopters. The helicopter drawings and paintings on

paper are also colourful, but more subtley so. The helicopters dive and float, swooping

through skies, hovering above the sea and the city, on unidentifiable paths.

At the level of the image, the helicopter series is engaging for its ideas of

repetition, exploration of the relationship between history and representation,

as well as a resulting reflection on the changing connotation of the helicopter

as machine over the years.

|

| Sabine Moritz, Sea King 70, 2016 |

Most

obviously, we recall the choppers of the Vietnam war, think of the use of

helicopters to deliver first aid, transport the police and the army, the helicopter

as a carrier of weapons and parachuters, as well as weapons. In spite

of the longevity of the intellectual and technical history of the helicopter as

vehicle and machine, Moritz’s drawings and paintings are spontaneous, sometimes

intimate and filled with emotion. The resulting multicoloured helicopters hang in the

air, fly through the sky, explode like bombs, are sometimes in the process of

being effaced from the image, at others heading straight for us. Some of them

are just a few lines, others, a frenzy of expressive gestures, flying through moody

skies, ostensibly evoking their potential surroundings, their mission. All these

qualities meant that the helicopter images were engaging and, for me, redeemed

the exhibition.

copyright all images Marian Goodman Gallery