|

| The Missing Link 4, 2013 |

Davis was one of those rare painters who could bring the political, aesthetic innovation, humour and poignancy, figuration and abstraction into a single frame. Davis's dexterous works exist in a difficult-to-place in between world, neither everyday reality, nor fantastical other worldly. The one thread running through all his work might be his commitment to the plight of invisible and marginalized people, evident in paintings populated by African Americans. But what is most striking is the way that Davis paints his figures. They rarely have discernible facial features, are typically shown in imbalanced frames or placed within fantastic narratives, in poses suggesting or depicting movement through environments, most often the street. And yet, we also see frames within frames everywhere in these paintings, the figures rarely feel entrapped, mostly because they are in motion.

.jpg) |

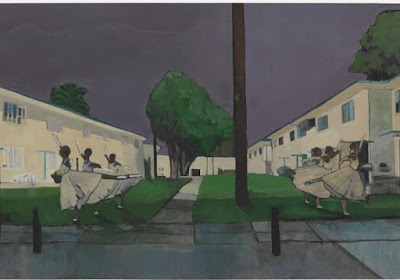

| Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque, 2014 |

The face as the mark of identity and recognition of the individual is typically removed from Davis's black figures. Faces are erased, masked, veiled, blurred, splashed with paint, silenced through the removal of the mouth. The figures' facelessness makes them both individuals in a challenging world, and metonymical black figures in American history.

|

| 40 Acres and a Unicorn, 2007 |

Another striking element of Davis's paintings is their surface. Beyond or in addition to the translucence created through his use of rabbit skin glue under paint and the scraping and washing of some canvases, surfaces are emphasized in scenes filled with reflections, squares and frames within frames. Drips, bleeds, shadows, cover urban streets and landscapes comprised of blocks of colour. This turns the backgrounds or space around the figures into areas as variegated and fascinating as the figures themselves. For example, in The Missing Link 4, a body of water in front of a modernist building captures the reflection of sky and concrete, merging with two figures playing. The texture of water and reflection is as compelling and curious as the housing project filling the upper two thirds of the painting.

Davis is one of those painters who begins from photographs and lens based media, mostly representing an interpretation of how black people are shown in these media. Several powerful paintings in the exhibition show the contrasts and constant flexibility and fluidity of Davis's paintings. Those beginning from anonymous amateur and family photographs find altogether different characters, relaxed, casual, at times exuding intimacy and connection. Other figures are isolated, alone, walking through worlds surrounded by painting and art, but unable to connect to other people. In 2012, Davis made a series of paintings inspired by midday trash television in which everything is constructed, stylized, and forced. These paintings, such as You Are ... are highly designed, the figures strategically placed, manipulated. Again, the figures are faceless, emphasizing the manipulations to staging, performance, and the cult of the TV personality and the de-individualization of the black participants.

|

| Painting for My Dad, 2011 |

Davis's pictures can also inhabit the other wordly: in paintings such as 40 Acres and a Unicorn we see ghosts and unicorns. In others modernism meets black aesthetics and mysticism, in which impossible things happen, such as ballerinas performing at a housing project, and in a painting such as The Missing Link 1, a young boy levitates in a garden as other children look on.

|

| The Missing Link 1, 2013 |

Davis's references are wide ranging and eclectic. We see a man walking through an urban environment that resembles a Rothko painting, an exhibition curated at his own Underground Museum in 2012 titled, Imitation of Wealth referencing the Doulas Sirk film in which a black girl passes as white - in which a white woman has a moral breakdown, in which white culture distorts the self-perception of black people. There are also references to Mondrian and the geometricization of the image, Friedrich and the wanderer, though Davis's journeys in the night. Marlene Dumas, Peter Doig, Luc Tuymans are also also recognizeable in receding figures in ambiguous landscapes.

%20The%20Estate%20of%20Noah%20Davis.%20Courtesy%20The%20Estate%20of%20Noah%20Davis%20and%20David%20Zwirner.jpg) |

| Untitled, 2015 |

While Davis's work is vast and diverse, intellectually rich, aesthetically innovative, and most significantly, committed to a politics of bringing unseen and unseeing people to visibility, as well as giving them the opportunity to see art, it's also extremely intimate. Viewers will sense the bond between three young men hanging out on a doorstep, surrounded by project housing, or two women asleep on a sofa. Perhaps most intimate are the paintings in which Davis himself is present, either literally as in a painting of his wife in a magic yellow costume or in a painting of a funeral in the distance, nevertheless within reach. It's impossible to see these paintings without noticing Davis's very personal spirit hovering around the walls. And it's impossible to see the exhibition without paying heed to the shadow of Davis's early death. As the exhibition presents it, the memory of Davis's art is clouded by death.

|

| Untitled, 2015 |