|

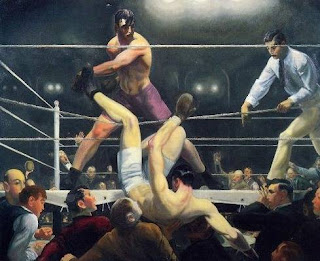

| George Bellows, Stag at Sharkey's, 1909 |

Hailed by the Metropolitan Museum installation of this

exhibition, George Bellows was one of “America’s greatest artists when he died,

at the age of forty-two from a ruptured appendix.” While I wouldn’t know to

argue with the Metropolitan, when I read this very big claim, the first thought

that goes through my mind and no doubt that of many visitors to the current

exhibition at the Royal Academy must be: Edward Hopper. Bellows and Hopper were

contemporaries and apparently studied together under Robert Henri in New York. And

for my money, there’s no question as to who was the greater artist.

|

| George Bellows, Pennsylvania Excavation, 1907 |

The exhibition at the Royal Academy is small compared to its

installation in New York and so it’s difficult to know whether or not Bellows

was more consistent than the examples represented here indicate. Or perhaps he

was on the way to greatness, but he never quite found his style due to his

premature death. The answers to such questions would be clearer if there was

more of Bellows’ work on display. My first disappointment was with the limited

size of the exhibition.

|

| George Bellows, New York, 1911 |

That said, there are some lovely paintings interspersed

throughout the exhibition, particularly, those that show the marginal life of

New York City in Bellows’: the boxing paintings of Sharkey’s, a well-known

joint hosting illegal activity at the time. Also impressive were the paintings

that depicted empty spaces in New York such as the foundation hole in the

ground that would become Penn Station, the Pennsylvania

Excavation, 1907. What I loved about these New York paintings was their

depiction of something that did not exist, the space, the emptiness, the void of

a world still to come. New York of this period is always depicted as a marvel

of modernist invention: skyscrapers, elevated subways, icons such as the

Woolworth Building, and the teeming turn of the century streets. But Bellows

represents the emptiness of the ground before all of this is built. Even when

he shows views along the Hudson and the East Rivers, it’s not the buildings in

the background that capture his eye, it’s the light on the water, the

reflections, the space of the river.

In paintings such as Men

of the Docks, 1912, Bellows interest in light at various times of day, its

reflections, its refractions reminds me of Monet – he wants to capture the

light as it reflects on the water, the night lights as they illuminate the pit

that will become Penn Station. In these particular works, like those of the

French impressionists, but with a much looser brush and a more dense use of

paint, Bellows primary interest is in light, in color, in paint. He is less

interested in the daily life of New York City. And so in the images of New York

we see Bellows lean in towards being a significant modernist painter: an

interest in form, in colour, in paint, light, and the simultaneous departure

from a fixation on figuration. But this promise is never realized. As Bellows’ career

progresses he becomes concerned with subject matter, and seems to leave behind

the fascination with questions of aesthetics. Similarly, he stays squarely

within the frame of representation, of traditional narrative painting. He never

reaches into the uncertain territories of abstraction. When we remember that these

works were being painted at the exact same time as Picasso was breaking apart

the picture plane, and completely abstracting the human body, Bellows becomes less

interesting and more derivative.

|

| George Bellows, Dempsey and Firpo, 1924 |

The other works that stand out in this exhibition are those

for which Bellows is celebrated: the boxing works. In Dempsey and Firpo, 1924, or Stag

at Sharkey’s, 1909, the boxers occupy the empty space at the centre of the

painting, illuminated as it is by color as light, in a reflection of the light

of the performance. Again, in these paintings Bellows shows great promise in

his fascination with light, with form, with paint. The entwined bodies are also

interesting because they create a movement across the canvas that again

gestures towards something original, but doesn’t seem to get fully realized in

the oeuvre as it is presented here.

This is work that is derivative all the way. It’s work that

lacks the uncertainty and the ambiguity that plagues and moves forward the development

of modern art. In addition, Bellows is not inventing anything new, nothing we

haven’t seen done earlier, usually in the late nineteenth century. Ultimately this

makes his work unsatisfying and not so impressive.

No comments:

Post a Comment