|

| Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruxelles, 1932 |

I was interested that this exhibition opened and closed with

images of not seeing. In the opening image, two men against a length of

hessian, one with his face to the fabric, the other looking away, distracted by

something to his right. As we leave the enormous exhibition on the top floor of

the Centre Pompidou, the final image rhymes with the 1932 photograph in

Brussels. And throughout, the photographer returns to images in which optical

devices are used to not look. The most memorable of these are produced on the

occasion of the coronation of George VI, 12 May 1937. In the wonderful array of

devices, ranging from simple mirrors through periscopes, telescopes and the

eyes of someone else, by turning his back on the procession that supposedly

captures the attention of the world, Cartier-Bresson might intend to capture

the crowds looking, but he ultimately finds them not looking.

|

| Henri Cartier-Bresson, Couronnement de Georges VI, 12 May 1937 |

Such novelties are typical of Cartier-Bresson’s oeuvre, and

indeed, they abound. But the disappointment is that they are never developed to

their full potential. In keeping with these momentary insights and delights, Cartier-Bresson

is a photographer whose work doesn’t ever set new standards or break new ground;

in fact, many of the images in this retrospective are familiar, often because

they do what many other photographs in the midst have become famous for. The

work of European photographers such as Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, Atget, German

1920s photographers, and so on, all produce sustained bodies of work that,

because of their focus, seem to have a greater impact on 20th

century photography. I say this, and yet, all of a sudden I come across this

series of photographs taken at the coronation of George VI and I begin to

wonder if Thomas Struth in the museum is so original afterall. At least

visually, compositionally, if not conceptually, there are resonances of

Cartier-Bresson in a number of the most celebrated contemporary photographers.

In a way that I don’t see happening in other, more celebrated experimental

photography of the European avant-garde, Cartier-Bresson’s work could be placed

as a premonition to the works of Gursky, Struth, Wall and other celebrated

realist photographers.

|

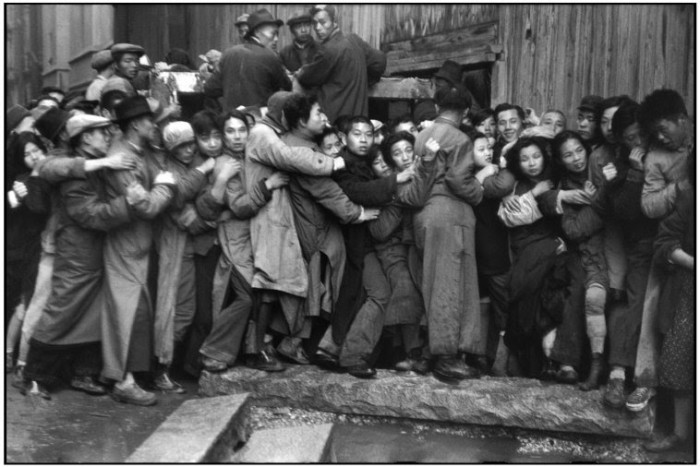

| Henri Cartier-Bresson, Foule attendant devant une banque pour acheter de l'or pendant les derniers jours du Kuomintang, Shanghai, December 1948. |

Cartier-Bresson travelled the world, in a way that few of

his generation could have done. Already in early 1930s, he was in Africa,

experimenting with the possibilities of photography. And there wasn’t a country

he didn’t seem to visit – spending time in Spain, Mexico, Russia, China, long

before tourism to these countries was even imaginable. I was struck by the fact

that Cartier-Bresson was always on the outside, arriving in Spain at the end of

the Civil War, witnessing the last days of the Koumintang, 1948, in Russia

after the death of Stalin, photographing Ghandi’s funeral. As if to imagine the

perspective of every traveller, Cartier-Bresson was always on the edge, looing

in, temporally as well as spatially, a marginalization that is echoed or

reflected in his images.

|

| Henri Cartier-Bresson, Salerno Italy, 1933 |

Among the most exciting and interesting are the early works

in which he uses walls, surfaces, spaces as screens for the capture of the play

of light and shadow. These have to be seen as somehow a premonition for the cinema.

The movement of bodies made into abstract figures in spatial configurations of

which the subject is light and shadow. Of course, this is the concern of every

photographer in the first half of the 20th century, but I admired

Cartier-Bresson’s courage to fill most of the photograph with a space or a surface,

thus transforming the intention and content of the medium.

|

| Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alberto Giacometti, rue d'Alésia, Paris, 1961 |

And then he returns to France and he gives us images and a

vision that lies at the heart of French cultural life and history. The image of

Giacometti, 1961 in the rain, in the last photograph before he dies has been

made famous by John Berger, for example. The young boy with a cheeky smile on

his face proudly marching through the streets with wine under each arm has

become an iconic image of French life, and that of jumping puddles behind the

Gare Saint-Lazare in 1932 have come to all but define the romance of Paris.

But what do we learn by seeing all of the photographs in

this huge retrospective? The blurb that accompanies the exhibition claims that

there are many Henri Cartier-Bresson’s. It means by this that he worked in a

multitude of different genres and styles. I want to suggest that it might mean

something else as well: there are times when the photographs appear derivative.

At other times, especially with the iconic ones, by seeing them in context, we

learn that there might be more going on than a single image can show. Often the

themes recur in different periods of his career, still being worked out and

revisited 50 years later. We also learn that his work is potentially

influential: the so-called anthropological images that show men and machines

woven together are a case in point: how many times have we seen this repeated

across the 20th century? It’s true that there is nowhere he did not

go, both metaphorically and literally speaking. And this exhibition gives us

the opportunity to find the jewels in a prolific career, in the same way that

he seemed to find the jewels in everyday street life in Paris, both in wartime

and at peace.

All images copyright la fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson