|

| L'Intérieur, directed by Claude Régy for the Festival d'Automne |

Maurice Maeterlinck wrote Intérieur in 1894 for marionettes, and

Claude Régy first directed the play in 1985 with a French cast. Tonight I saw

Régy’s revisited production with Japanese actors from the Shizuoka Performing

Arts Center. Though I can imagine the play with marionettes, it’s hard to

imagine the fragmented, almost mechanically pronounced words of this short play

being spoken in French by French actors. The Japanese cast, speaking in very

resonant, almost musical tones was perfect. It was as though they held the

resonance of Maeterlinck’s words translated into Japanese in their voices which

were, in turn, held in their bodies as vessels. The spoken dialogue is sparse,

simple, factual almost, and yet it too, like the voices that reverberate in the

bodies of the actors, is profound. They announce statements that expland well

beyond the events taking place on stage, such as the old man’s warning: « Prenez garde ; on ne sait pas jusqu’où l’âme

s’étend autour des hommes »

|

| L'Intérieur, Directed by Claude Régy for the Festival d'Automne |

The beauty of this production is in the

slow, silences of the staging. A family—a mother, father, two girls and a

child—are in their house, and the most significant event in the moment is that

their child sleeps. “Outside” the “house,” a separation of spaces that is bare,

but distinct, on Régy’s stage, some people comment on what is taking place

inside the house. And then, they must tell the family that one of their

daughters has drowned in a nearby pond. But how?

|

| L'Intérieur, Directed by Claude Régy for the Festival d'Automne |

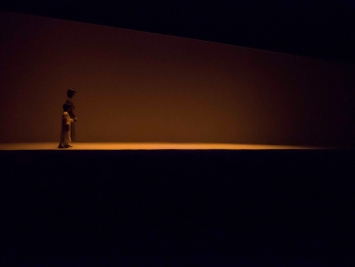

It’s a play about death. Played out in the

tension between inside and outside the house, the Japanese actors in this

version of the play are like ghosts. Dressed in simple clothes, most of the

time, they walk on white sand, slowly so that we can hear every footstep, the

sand underneath their shoes. The silence of the step was loud in a theatre full

of people so still. The silence of the step became a language of its own. The

light changed very subtley, slightly, so there were times we could see the

actors’ faces, until it faded away again and they became silhouettes. And there

were times when the translucent light of the night was blue, at others, the

characters were walking slowly, through a world of yellow.

Although the words are profound, I was struck

that in a piece focused so specifically on death, how it happens, how to live

in the presence of death, what it means, how it transforms the lives of those

around it, and so on, there was a distinct absence of melancholia, even

mourning. In fact, all emotion was held in the performance, as well as the

meaning of the words. Apparently, Régy and the actors have no language in

common. He directed a cast without speaking their language. Surely this must

contribute to the importance of the resonances and sonorities of the language, making

them as heavy as the meaning of the words? Together with the meditative like

movements and the haunting, mysterious light, the unique use of a foreign

language created an indistinction between conscious and unconscious. This

created further distance from the language, allowing the light, the stage, the

characters’ movement to fill spaces beyond language. And it was in these spaces

that the most significant things were communicated.

No comments:

Post a Comment