|

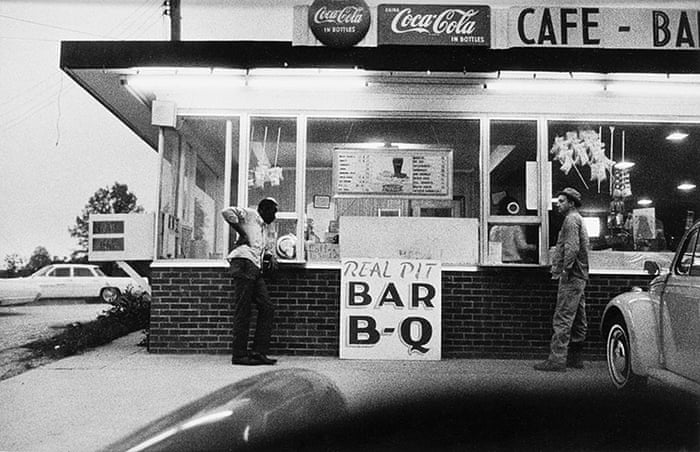

| William Eggleston, Untitled (A Cafe in Memphis), Memphis, c. 1968 |

The epigram to the catalogue’s main essay

quotes Eggleston: “I think of them as parts of a novel I’m doing.” The

quotation finds Eggleston reflecting on his series of photographs, as though

next to each other, the narrative unfolds. As I wandered this small, but rich,

selection of Eggleston’s work I was fascinated to see that each image tells a

story, each image contains a long, and often mysterious, narrative that begins

with the suggestions in the image and continues in the viewer’s imagination. Even

before they are put in their series, within each frame, there is a story to be

told. And if we recognize early on the debt owed to Eggleston by photographers

such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff, what the contemporary photographers

don’t do is also very clear.

|

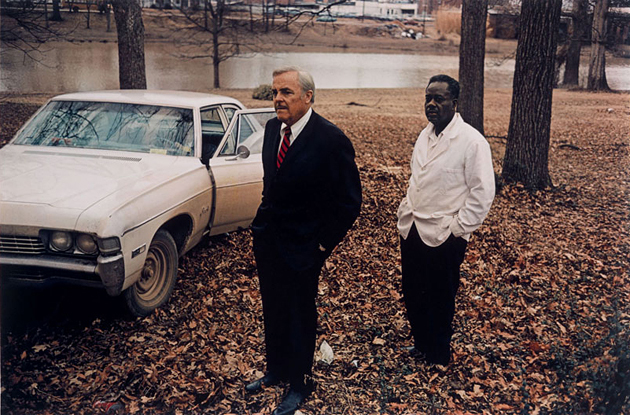

| William Eggleston, Untitled (Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in Background) 2011 |

Eggleston’s photographs tell stories in a

way that photography in a post-photographic world does not. A man’s hand

picking something off the ground reflected in the fender of a car, a black man

and a white man standing together in what looks like a remote location, a car

with its door still open behind them, or an old man sitting on bed with a gun

at his finger tips. All these images are swelling with a story that’s not yet

told. All these images hold us before

them, conjuring up the narratives that have led to the moment Eggleston finds

in the image. In other photographs, the mystery is ignited and the story begun

through the framing. It’s rare that Eggleston includes the whole object in the

image, mostly it’s parts of objects, places, even people, that come into his

frame to create textures, shapes, patterns, and thus, to give them a before and

an after. Our imaginations are tempted.

|

| William Eggleston, From Los Alamos Folio 1, Memphis (supermarket boy with carts), 1965 |

So much of what Eggleston is doing, so much

of what makes these works not possible in today’s post-photographic world lies

in the materials of his art. Everything in these photographs begins with the

richness and materiality of their color. The color is not only vibrant and clear,

but the colors themselves are unusual for today’s viewers. The pinks and

yellows and cobalt blues are the result of Eggleston’s use of the dye transfer

process. A boy pushing shopping trolleys, a woman in the car with her children,

even a television bathed in the yellow light of the setting sun are so rich

that on seeing the photographs, it’s as though Eggleston discovers the

existence of this magical hour of the day. The yellows, pinks, greens are

bright, intense, deeply saturated and with not a trace of disintegration over

the years. Eggleston discovered the dye transfer process in the early 1970s as

a printing process that would allow for the reproduction of intense colors: in

its original use for advertising, the brighter the color, the more attractive

the product. Eggleston takes uniqueness of dye transfer—its larger color gamut

and tonal scale than any other process—and sees the world through its possibilities.

Again, it’s as if the world he discovers did not exist before he saw it through

the lens of his photographic process.

|

| William Eggleston, From Dust Bells, Vol 1 Memphis, c. 1965-68 |

But it’s not all process, because Eggleston’s

photographs are anything but advertising. It’s something to do with the fact

that the places and spaces, the objects and even the people are rarely

photographed in their entirety. Composition is of utmost importance to the

poignancy and odd simultaneity of mystery in these photographs. Similarly, he

points his camera at the decay that he finds on the streets of the 1970s

American South. The overwhelming sense of decay to the places and objects and

surfaces that fill these photographs put them at a remove from the advertising

images for which the dye transfer process was made.

|

| William Eggleston, From Los Alamos, Folio 4 Louisiana, c. 1971-74 |

The images are everywhere about the

American South. When a black man and a white man lean at two different service

windows of the same Real Pit Bar B-Q joint, for all the perfection and

suggestion of the harsh fluorescent lighting, there’s one thing we see: a black

man and a white man leaning at different windows. This is the American South

after all. And the gentleness of the light on a wet street in Los Alamos

(maybe) cloaks four women on a street corner, making them anything from friends

out at night to prostitutes waiting for business. It’s difficult to say which. There’s not much

sadness in Eggleston’s worlds, just age and many sets of stories that we cannot

know, but which are begun through the suggestions of what finds its way into

the image.

No comments:

Post a Comment