|

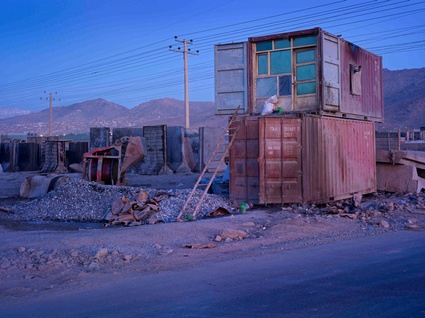

| Simon Norfolk, A Home Made of Shipping Containers, Kabul |

I had many questions of this vast

exhibition of photography. Is it really about the intersection of photography

and architecture, or is architecture the thread that loosely holds together a

certain history of art photography in the twentieth century? The photographers

collected here are among the most celebrated of the last 100 years, and it’s

really exciting, if overwhelming, to see all their work together. Strictly

speaking, however, a number of the photographs in the exhibition were not about

architecture. Works by Berenice Abbot, Walker Evans, and later on, Simon

Norfolk and Nadav Kander, among others, are exemplary of the development of

photography and its negotiation as representation of space over the past 100

years, but they are not representations of architecture. Space, light, surface,

and their intersection with photographic representation are the more likely foci

of Constructing Worlds.

|

| Berenice Abbott's photographs in Constructing Worlds |

My second question for the curators is the

size of the exhibition. As I say, there is no doubt that it is a treat to see

all these great photographs in one space, but to be honest, I found it too

much. It is impossible to get an overall sense of over 250 photographs by 18

photographers, that span the 20th and 21st centuries, as

well as every continent on earth. With this challenge in mind, here are my

thoughts.

What stood out for me was my introduction

to some photographers I wasn’t previously familiar with and to those by others

whose other work I know well. Hiroshi Sugimoto’s blurred and confused spaces

and places of erasure are breathtaking. And they become haunting, unforgettable

when we learn that they are actually representations of the World Trade Towers

in 1997, four years before they were destroyed, it is as though Sugimoto knew

the fate of the twin towers. Sugimoto’s long exposure technique has produced a

very different, but nevertheless, powerful result in these huge black and white

images.

|

| Lucien Hervé, High Court of Justice in Chandigarh, 1955 |

Upstairs, Lucien Hervé’s photographs of the

High Court of Justice in Chandigarh, India 1955 stood out for their abstraction

among works that were, for the most part, interested in some form of

documentary realism. Hervé’s almost delicate images are both an ode to the

medium of photography as no more and no less than images of light. Hervé more

than anyone else in the 1950s represented in the exhibition is pushes the image

in its relationship with architecture into abstraction through silver gelatin

prints. And simultaneously, as he photographs Le Corbusier’s radical building,

he finds an architecture as well as a mode of representing it that breaks new

ground in the 20th century.

|

| Guy Tillim, Apartment Building Avenue Kwame Nkrumah Maputo Mozambique, 2008 |

By the time I reached Guy Tillim’s

photographs downstairs, I was convinced that photography is the superior medium;

its flexibility, vast possibility and ability represent, reconstruct and

document all at the same time. And yet, I was frustrated again because Tillim’s

familiar sensuous, but rough and organic surfaces are almost de-politicized when

we don’t get any information regarding the production and more importantly, his

printing process. Tillim’s technique is everything. To be sure, of course, the

images are about the dilapidated, derelict government buildings and luxury

hotels, the state of decay of his native post-colonial Africa. But the blunt,

hard vision of Africa is brought to life through his use of pigment ink on

cotton rag paper to give the buildings a wet texture that is key to their

political edge. Along the same lines, nothing is mentioned of Gursky’s digital manipulation

of the image in production and post-production to stretch the underground

subway station of Sao Paolo, Sé

(2002) in his characteristic rendering of an everyday space of capitalism, an

isolated superficial structure.

|

| Nadav Kander, Chongqing IV (Sunday Picnic), Chongqing Municipality 2006 |

Nadav Kander’s photographs of the Yangtze River

and the industrial developments that have taken place there are mesmerizing. Their

empty, effaced backgrounds, the traces of structures that could be from the

past or the future, it’s difficult to say which, are at first glance, almost

Romantic. And then up close, the enormity of the structures, their overwhelm of

the people takes over, becoming ever more noticeable. In what is unusual for

the photographs in this exhibition, people existed in the reconstructed worlds

of China, but they are always dwarfed by the development of industry along the

Yangtze. And for us, who are so aware of the imperative to take care of our

landscape, Kander’s photographs show the violation of a landscape that otherwise

has no hope. Thus, after time, the transformation of the river is like a

descent into hell shown in Kander’s images.

I also enjoyed seeing Simon Norfolk’s Afghanistan images. His excessive use of

filters simultaneously creating a superficial vision of bullet scarred, war

torn Afghanistan, as well as exposing how the same spaces are repurposed to

functional everyday uses. There is no mercy in this world – sun and light may

shine brightly on seductive landscapes, but they are populated by buildings and

worlds that have been destroyed. The irony is everywhere in Norfolk’s images.

|

| Luisa Lambri, Darwin D. Martin House (1905) designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, 2007 |

Luisa Lambri’s negative spaces were

compelling and lyrical, as she finds what cannot be documented, what is left unspoken

for in the built environment. Her prints explore corridors, doorways,

thresholds, the caverns and crevices that might otherwise be ignored. Lambri’s are in the same vein as Hélène Binet’s

captivating images of the Libeskind Jewish Museum in Berlin. But where the

latter creates dimensionality and volume through filling space with light,

Lambri does the opposite, closing down the spatial environment so that only

what is otherwise invisible is traced in light. I was interested to see that

these two examples of work that no longer expose the structures and surfaces of

the architectural, are by women. It’s women who are interested in space, in the

unsaid, the invisible.

| Hélène Binet, Jewish Museum, Berlin, 1998 |

And in this, their work strongly resonated

with that of Berenice Abbott upstairs. In the 1930s, the student of Man Ray was

interested in finding the spaces that are completely taken up by buildings,

closing out sky. Abbott’s photographs were about the density and intensity of

New York, the city it would become, sculpted through the intensity of the

relationship between light and the camera, the chiaroscuro able to be created

through the specificity of the photographic medium.

No comments:

Post a Comment