|

| Berthe Morisot, Young Woman in Grey Reclining, 1879 |

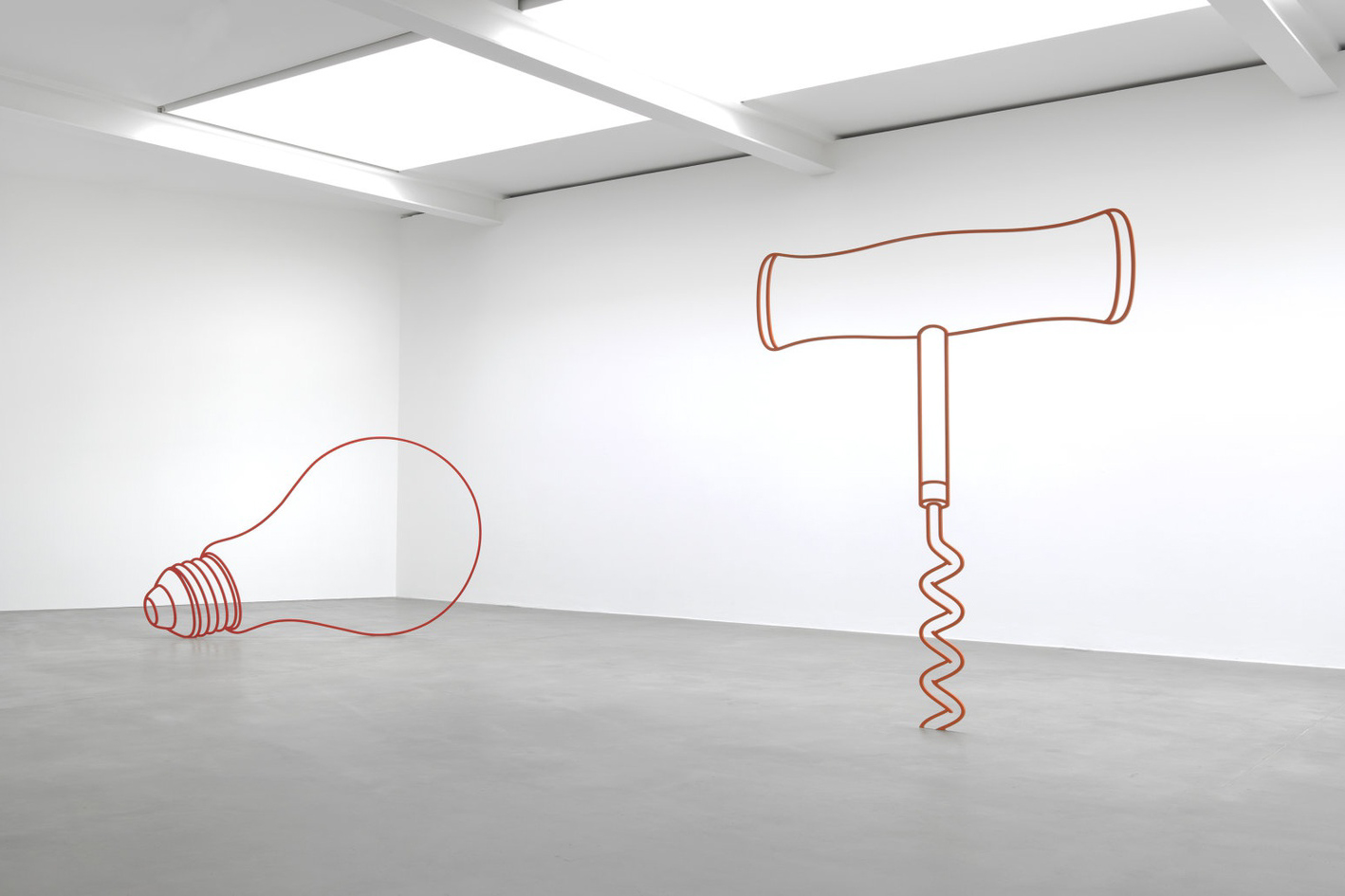

This lovely

exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay is a summer crowd pleaser. It’s one of the most

coherent exhibitions I have seen this year, has great appeal for tourists

looking for Impressionist colour and light, and opens new horizons for art

historians and critics. I do have one small issue though; its installation upstairs

in the first floor corridor galleries that don’t all connect to one another. The

exhibition in multiple single entry rooms interrupts the flow as we have to go

in and out of the exhibition. Otherwise, it’s a delight

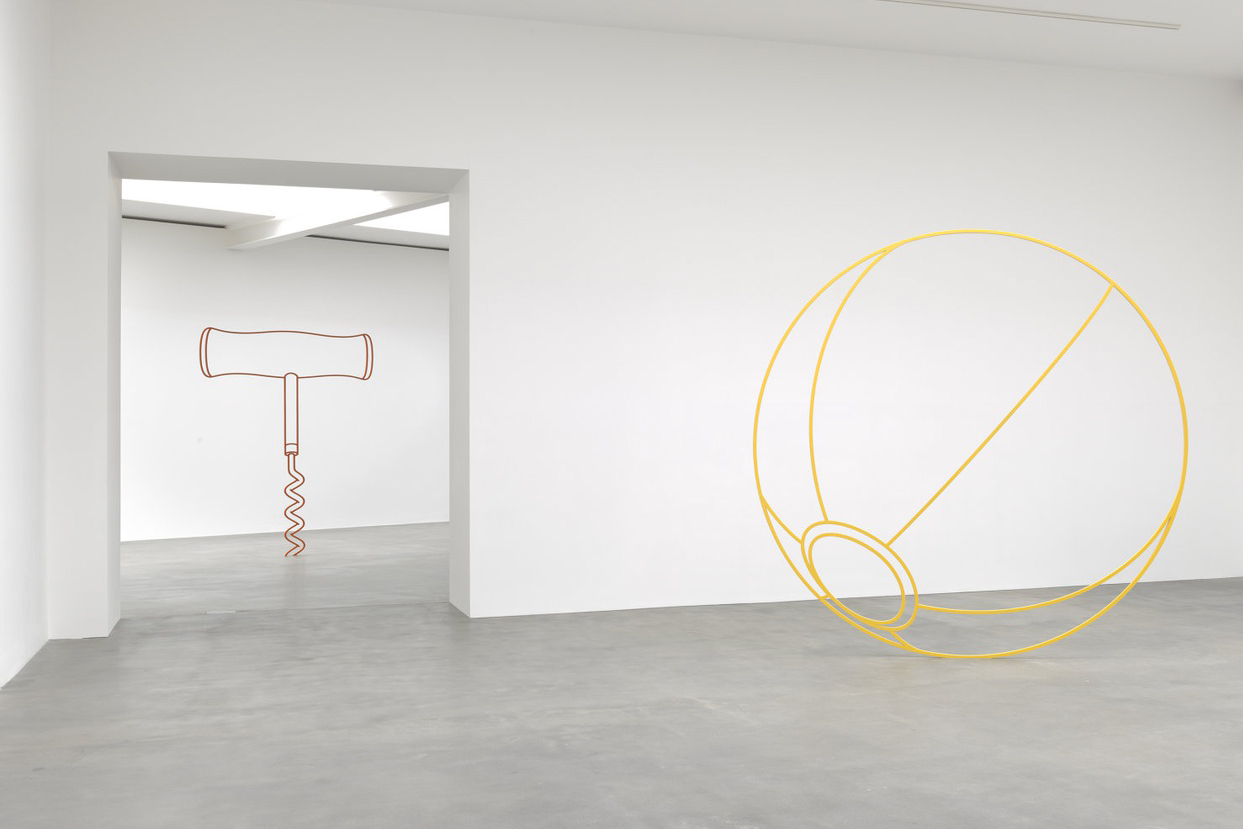

|

| Berthe Morisot, Cousant dans le Jardin, 1881 |

Of course, the

thing on our minds as we enter the exhibition is gender. Few people know Morisot’s

work because, together with Mary Cassatt, she was a woman. Everyone knows

Renoir, Monet, Manet and Degas, and perhaps other of the male Impressionist

painters. However, Morisot was all but forgotten by history until Linda Nochlin

revived interest in the 1990s. It’s worth noting that Morisot was selected for

exhibition in the Salon from 1864 onwards, giving her some success in her

lifetime. But critics dismissed her as amateurish and confused, particularly on

account of her tendency to leave areas of the canvas without paint. Much is

made of this by the exhibition text, but we will also remember that the male

Impressionists were also rejected at the time for their then radical approaches

to the canvas. So it’s not exactly correct to claim that her work was rejected

on account of her gender, even if that’s what critics claimed. Nevertheless, visitors

to the Musée d’Orsay will discover why the very qualities that early critics

identified as evidence of her uncertainty and lack of skill are in fact

indications of her control over the canvas and subject matter. The empty space

of works such as Cousant dans le Jardin (1881)

give a sense of looking through a keyhole at a moment in time. And in others,

the centrality of the figure creates an intensity to the paint and the

depiction which becomes amplified by the empty edges.

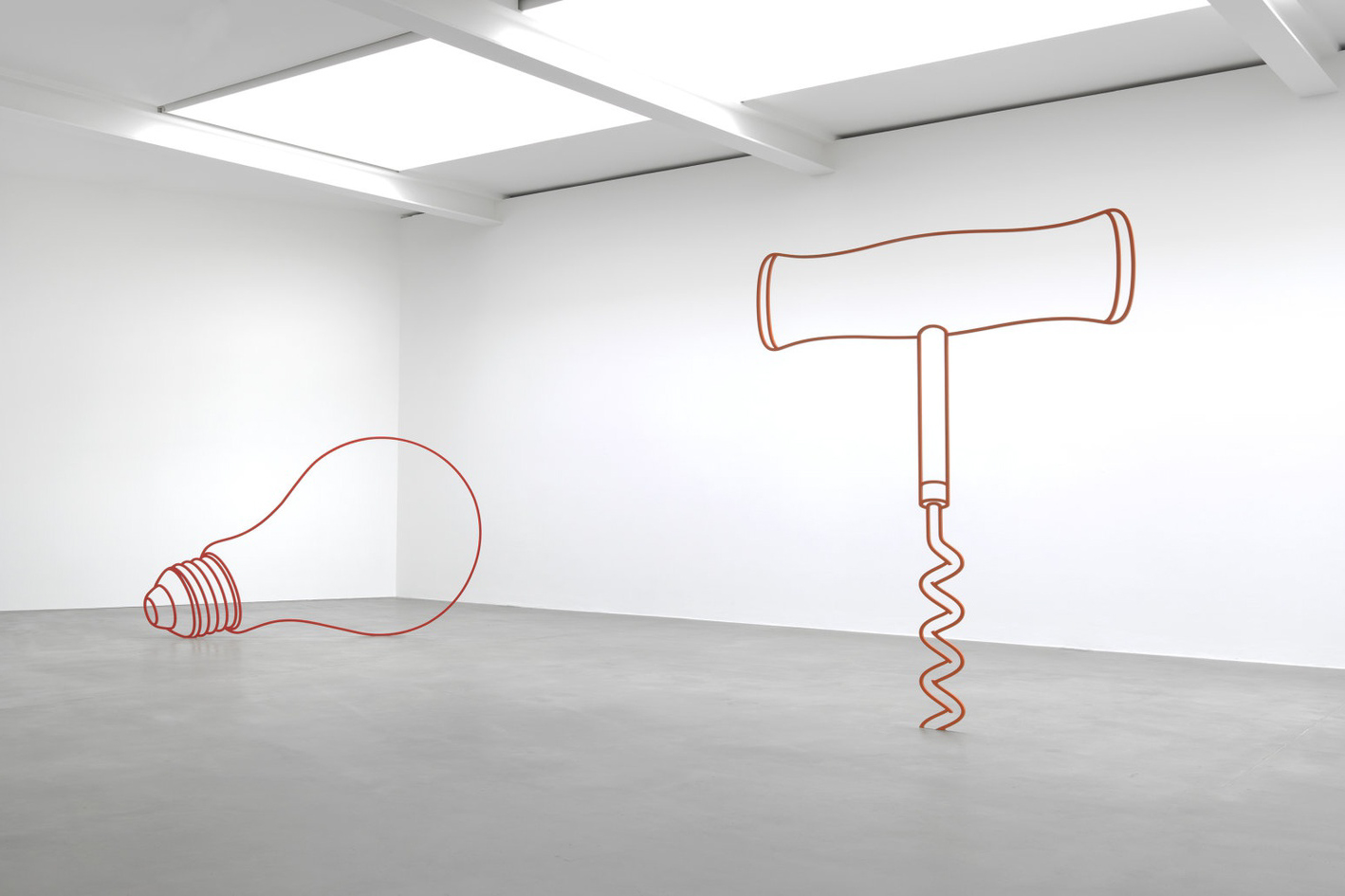

|

| Berthe Morisot, En Angleterre, 1875 |

For me, the

most impressive paintings were those using mirrors and windows. For Morisot, as

for many of her Impressionist brothers, there is a full flattening out of the

canvas. She does this by using fabrics and clothes to close down space of the

room, where dresses become indistinguishable from sofas and curtains continuous

with the walls behind them. Similarly, the space is often framed so that we

don’t see the edges of the room, and outdoors, we see no sky. Rather, the space

is shut down by the sides of the frame. Morisot goes one step further when she

adds mirrors and windows that both extend the spaces outwards, and yet, reflect

back on themselves. Thus in an image such as En Angleterre (Eugène Manet à

Isle de Wight), 1875, the man is caged by the window as he looks out to the

harbour. At the same time, the woman and child on the other side appear against

the window. There’s no distance between him this side of the window and them in

front of the fence on the other side of the garden. Or in La Psyché, 1876 in which the body mirror extends the space, but

also throws the image back through the blur of the background to her figure, a

background that is continuous with the curtains on either side of the mirror.

|

| Berthe Morisot, La Psyche, 1876 |

Coming back

to the question of gender, critics such as Linda Nochlin who “rediscovered”

Morisot in the 1990s—forming text panels accompanying the paintings—are not

fully adequate to the description of what Morisot was doing. The idea that

Morisot’s vision is a private one of indoor intimacy, the woman’s world, or

that the paintings of wet nurses and domestic workers somehow reference

Morisot’s own work as a painter, fall short. It’s true that Morisot paints

images of women reading, darning, picnicking, in the garden and so on. It is also

true that her’s is a women’s perspective. However, there’s more to these

paintings. In the push to abstraction of the rapid and sketchy brushstrokes,

Morisot appears to use her subject matter as a vehicle to explore the dynamism

and perspectival transgressions of representation that were around her at the

time. In other words, she uses her subject matter as a way to engage with the

energy of modernist painting in the late-nineteenth century. And it’s not only the

depiction of women indoors that marks her paintings as different from those of her

male counterparts. In spite of the very painterliness of her images, there is

always a sense of the photographic. The centrality of the figure in a

disintegrating background (as if out of focus), the presence of every aspect of

an image fixing a moment out of time, and the repeated use of the figure

merging with foliage, as if in a masking are all traits of photography, the

invention of the day.

|

| Berthe Morisot, Laundress Hanging out the Wash, 1881 |

Nochlin claims

that Morisot’s frequent representation of working woman are a mirror of the

artist as a worker. We must however remember that what we see in these worlds is

the very privileged perspective of upper class life in Passy. There is no

suffering for the working women in these paintings. I think, by comparison, of

Daumier’s women on the rue de Rivoli, Millet’s women in the fields, or women

who are forced into work by the progress of modernity. By contrast, Morisot’s

women are children’s nurses, maids sewing, or kitchen hands. All work is gentle

and leisurely in this secluded bourgeois world; we see none of the sacrifices

made by the wet nurses, the scullery maids and nannies. Morisot is not just any

woman; she is of the privileged classes, married to Édouard Manet’s brother,

with money and art world contacts. Her representations of women match this

privilege.