François Pinault is known for his eye for contemporary art that challenges its world. Thus, it is no surprise to see that all of the works on display in these inaugural exhibitions are concerned to challenge the purveyors of power. Whether it be the excoriating portraits of Marlene Dumas and her fellow South Africans, such as Kerry James Marshall, or Ryan Gander's mouse appearing to have eaten its way through the wall by the elevator, the works are constantly challenging all that their surroundings. Dumas's depictions of violated sexuality, racial injustice, and brutality of the powerful over the powerless scream at us from their walls. There is no mistaking what these exhibitions want to convey. The building may have been constructed at the intersection of industrial modernity and colonial power, but art of the centuries since has unravelled the legitimacy of this power.

|

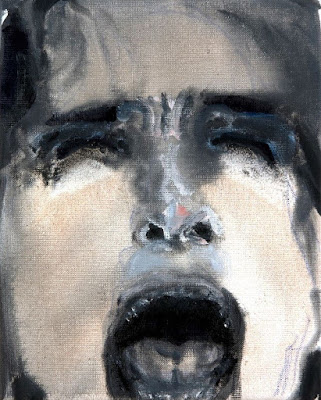

| Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (Paula), 2012 |

From the very first steps inside the museum, the challenge to power is not simply represented, but felt. Urs Fischer's irreverence sets the tone. His central installation is both monumental and searing in its critique of the monumentalism of art, commerce and white male sexuality—effectively everything that the history of the Bourse de Commerce encapsulates. As we contemplate the installation, we realize that Fischer and his friend Rudolf Stingel are concerned to undo the narrative of power that we look up to. Beneath the grand narrative of colonization and the triumph of French nationalism of the ceiling frescoes, Fischer has placed a wax sculpture of Giambologna's Abduction of the Sabine Woman (1579-1583). The original sculpture, on view in the Loggia in Florence, shows a woman desperately struggling to free herself from her male captors. Demonstrating an irreverence and dismissal of its history, Fischer's work is a candle that will burn for six months. Already, when I visited one month after opening, the captor's head was in a state of disintegration. Surrounding Fischer's statue, his Stingel has installed wax—also in the process of melting—chairs of all kinds from around the world. Board room chairs, airplane seats, indigenous seats. Thus, the artists transform monuments into ephemeral objects that, ultimately, cannot be looked up at or down on. They are in the process of disappearing.

|

| Reflections of the late afternoon sun |

Speaking of chairs, Tatiana Trouvé's eight chairs, The Guardian dotted throughout the museum are one of the delights of the permanent exhibition. The chairs cast in bronze, copper and filled with the bags, shoes, pillows and books in marble and onyx are all at once curious, inspiring, sensuous and sad. It is as though the owner of the objects under, next to, or on the chairs has just stepped away and will be back any moment. Trouvé's use of materials against themselves—marble that looks as soft and comfy as the pillow it represents, books made of onyx that we feel the urge to turn the pages—creates an impossibility. The impossibility of the materials and the absent owners come together in intriguing, playful sculptures that somehow distract us from the paintings in the room. The chairs are also indicative of the frequent shifts of attention that we experience as we wander—iron lattice reflections on the cupola's frieze, a double staircase for operation of the wheat exchange, a medici column, and arched passageways. Trouvé's chairs tell of yet another history having taken place in the building. There are so many wonderful works on display that it's difficult to pick a favourite, but I was delighted to see Louise Lawler's installation, The Helms Amendment series (1989). The 94 black and white photographs of a plastic cup, each given a supporting senator's name and state —red for Democrats and blue for Republicans. Among other things, I didn't know that the Democrat/blue and Republican/red colour coding for American political parties wasn't introduced until 2000. The photographic series was Lawler's response to the US Senate vote in favour of an amendment to government spending, which in 1987 saw the refusal of funding for AIDS education, information and prevention materials, under the pretext that it encouraged homosexuality. Most powerfully, the six abstainers and naysayers do not get a cup in Lawler's series. A quotation from the amendment accompanies the naysayers names: "none of the funds made available under this Act to the Centers for Disease Control shall be used to provide AIDS eduction, information, or prevention materials and activities that promote or encourage, directly or indirectly, homosexual sexual activities."

|

Louise Lawler, Helms Amendment, 1989, detail

|

The seemingly benign empty plastic cup, its reflection, and the black silence surrounding it incites viewers to reflect on the deep political divisions of our time. In addition, the fact that 94 of the senators voted to uphold the amendment surely prompts wonder and outrage at the ongoing violation of human rights and senseless discrimination of the political system. The work's eerie relevance in 2021 gives further cause to pause at the mechanisms and institutions of power and manipulation that are critiqued throughout this, Paris's newest museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment