|

| Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014 |

British wonderboy Ed Atkins has an

installation at the Palais de Tokyo that anyone who claims to keep up with the

art world will need to see. At 32, Atkins has made quite an impression on those

who matter with exhibitions at MoMA, a single artist show at the Serpentine’s

Sackler Gallery, a solo exhibit at the Tate Modern, the ICA, Venice, and the

list goes on. The impressive CV was enough to entice Irina and I to see Bastards following our visit next door

to what was, by comparison, the genteel Fontana exhibition.

|

| Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014 |

Ribbons (2014), adapted for the Palais de Tokyo, is a three channel, high

definition video installation in which Atkins explores the latest language in

image production. Morphing between filmed footage and digital imagery, Atkins

uses everything from traditional video and cinematic strategies —blurring,

lens-flares, scratches, sound and image editing — to the latest computer

graphics for which he apparently does all his own coding. There’s no doubt that

the technical dimension of Atkins work is inspiring. His command of the image

and its multi-form production is impressive, speaking to the agility of image

integration and technical literacy of his generation. Likewise the form is

exciting in its reflection of the way that we receive and process visual

information.

|

| Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014 |

Irina and I, two women of a different

generation, may not have been able to identify with or in the images, but both

of us were convinced that Atkins’ Ribbons

was more relevant and more interesting than Godard’s latest film, Adieu au Language (2014), a film we had

seen the week before. Atkins, unlike Godard who claims to converse with the

latest image technology, actually uses the most contemporary visual and sonic

language as he moves in and out of as well as along a spectrum of digital

possibilities. Atkins creates a more convincing adieu to language than Godard’s

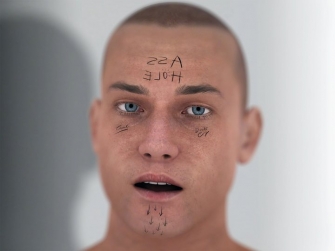

soporific dabble with 3D imaging. Words for Atkins are text messages, made

visual before disappearing to be replaced by the next words or image, they are

reduced to marginalia, scribbles on a body, snatches of poetry, quotations

emptied of meaning, unfinished.

|

| Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014 |

The protagonist — who seems to shift in and

out of identification with Atkins is a troll, apparently. But mostly, he is

obsessed with his sexuality, distractedly getting involved with those great

British pastimes — getting drunk and falling over—until he is deflated,

literally, through computer generated animation. The Palais de Tokyo identified

the character in the three narratives, on three large discrete screens, his

voice resonating through the space, as Atkins. But it isn’t, it’s an actor.

Admittedly though, the identity of the actor is not important, in fact, the

confusion of identity reinforces the anonymity of the artist. It might as well

be Atkins, his alter ego, bellowing with pride and then deflated, defaced or

effaced. He is often surrounded by pint glasses, pouring drinks, being drunk,

getting high, sticking his tongue, his nose, then later, his penis through a

hole, wedging himself under the table. It is all about Atkins even if he is not

in the videos.

|

| Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014 |

The sound for the exhibition was brilliant.

When Bach’s St Matthew’s Passion was sung, the three voices resonated and

intertwined through the sound of the three different screens. And then, at

other times, we are completely surrounded by the sound when standing before the

screen to which it relates, and there is no interruption of the sound from the

other screens. Bach mutates into burps and farts and then Randy Newman who is,

in turn, interrupted by email alerts.

If technically Atkins’ installation is

brilliant, even mesmerizing, conceptually it lacks maturity. We also become

aware of Atkins’ identity through the musings and convolutions of sound and

image. With his obsessions of drinking, speaking, fucking, with an occasional

search for reality, Ribbons comes

across as the work of a young, ego-centric heterosexual artist who does not yet

have the depth to allow for the resonance and profundity of those he quotes,

such as Blanchot and Lacan. As captivating as it was, the irony wasn’t strong

enough to convince me that this is anything but a straight boy’s glib view of

the world. Atkins could develop his work in a number of different directions,

and his success as an artist will depend on which of these he chooses. But for the

moment, to me, he’s still a 32 year old young man with work to do.

All Images Courtesy of the Artist

No comments:

Post a Comment