|

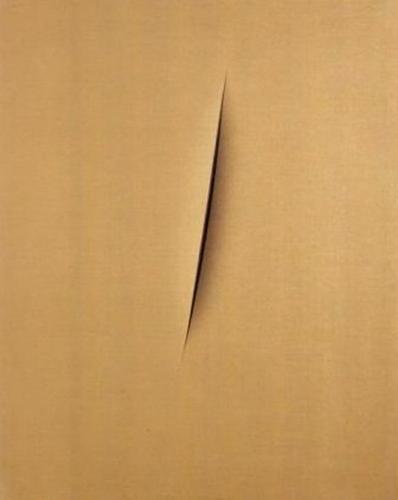

| Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attesa, 1960 |

I had heard not very good things about the

Lucio Fontana exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. At

dinner last week, a friend looked appalled as she announced that over half the

exhibition is taken up with ceramics and sculpture. It’s true: it took Fontana

a long time to find his unique contribution to the history of art. In fact, it

wasn’t until the 1950s, that is, halfway through the exhibition, that he starts

putting holes in his canvases, and slicing them open. Up until this point his

work is derivative and not very interesting. Even the early cut works are not

so exciting, appearing as little more than thinly painted canvases with holes

in them. It’s not until the 1960s, when he does nothing but cut and making

holes in the canvas — the final rooms of

the exhibition — that the works come to be anything more than mediocre works

with theoretical or historical rigour.

|

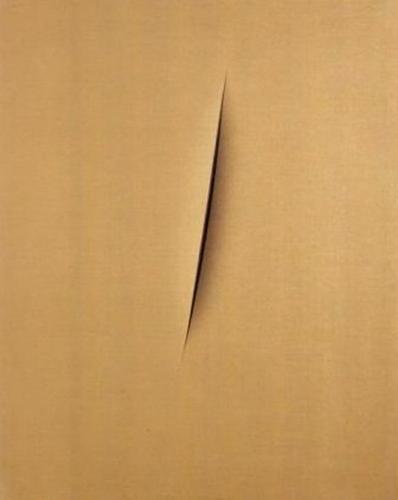

| Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1966 |

One thing that surprised me (once I got to

the final rooms of the exhibition) was that even though I always knew Fontana’s

cuts are the ultimate iconoclastic gesture, I didn’t realize how little they

have to do with painting. At times, the canvas is not even painted, but a piece

of thin, almost transparent fabric covers the canvas and so the canvas is not

even cut. The works are almost all entitled Concetto

spaziale (Spatial Concept) thereby indicating the three-dimensional,

articulation of an object in and as space, rather than as two dimensional

images. And yet, while they are not about painting, the works are about the history

of art. Fontana’s slicing open of the canvas speak a violence, disrespect,

defacement, denigration of all that can be imagined by such a gesture. The act

of cutting the face of the canvas, even when there is nothing on the canvas, is

perhaps the most definitive act of iconoclasm.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, New York 10, 1962 |

Along with the displacement of the canvas

as image, there is nothing to look at, even though the visual appearance of the

canvas is always different from image to image. Visually, each spatial concept

is like a repetition of those on either side of it. Whether there is one cut or

a series of cuts, it doesn’t seem to make a difference, and we seem to be

looking at a single concept being reiterated over and over again. And then, in the

last few rooms — the 1960s — everything comes together a matter of years before

Fontana dies. In the end, the works are about the sense of touch, they are

erotic, they are gendered, imaginative, and somehow transport us to another

level of experience. The cuts become a moment that we sense, an anterior

moment, because it is as though we are looking at that moment of cutting

itself. We get to feel the curve of the gesture of slitting – it’s incredibly

sensuous. The cuts as the trace of the artist, are sensuous, physical, and they

are no longer revealing violation, but some kind of spiritual belief, a calling.

As Fontana approaches the end of his life, the cut is a creation, not a

violation. But of course, it is still a violation because it slices the canvas

open, however lovingly. And there is no mistaking that these are the gestures

of a powerful male artist, making incisions that remind of female genitalia. Around

the edges of the holes the paint is coagulated, where it has dried up, it is

thick, we want to touch it, it is so tempting it arouses desire.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, 1962 |

In the final room of paintings, the holes

on the canvas become bigger, they become gorgeous until there are more of the

holes than the canvas. Finally, we realize, Fontana is an artist exploring the void.

What in the early years was about making painting into sculptural, expressing

the materiality of the canvas through its incision, by the late 1960s, Fontana

is building sculptures that are constantly cutting away the material and all

materiality, to find the nothingness. While the museum blurbs kept emphasizing

Fontana’s interest in space and spatial organization, the works also strive

towards its opposite, a non-space, absence.

|

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale. la Fine di Dio, 1966

|

It’s a spiritual practice – he’s actually a

kind of romantic artist, not as modern as I have always assumed. At least,

where the work might be modern in its material challenge to the identity and

status of representation, especially painting, the most interesting dimension

is the spiritual. Fontana strives for some kind of transcendence himself and we

get to sense that journey.

Images courtesy Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

No comments:

Post a Comment