|

| Theo Kamecke, Moonwalk One, 1970 |

Moonwalk

One is in many ways, the ultimate American feel

good movie. But as Discovery Channel-type documentaries go, it is a unique treasure

that, because it is now 45 years after the fact, can almost be forgiven its

“America the great nation becoming even greater by winning the space race”

narrative. The director, Theo Kamecke, was commissioned by NASA to make a

documentary of Apollo 11’s 1969 trip

to the moon, and for the purpose, he was given access to launch control, mission

control and all NASA’s technical footage. The result is a compilation of stock

and shot colour 16mm footage blown up to 35mm. The film was shelved having attracted minimal attention at the time, and recently rediscovered, digitally remastered and re-released. For cinema lovers, Moonwalk One is a treat from beginning

to end.

|

| Theo Kamecke, Moonwalk One, 1970 Making space suits |

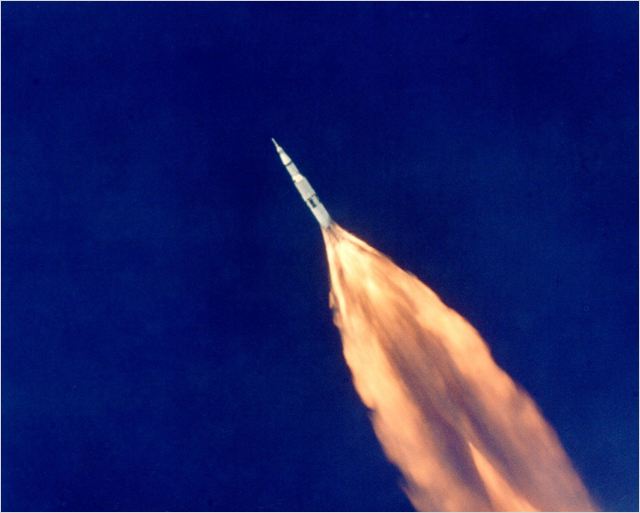

Anyone familiar with the aesthetic of 16mm

Kodak film from the late 1960s will be able to guess why this film is so luscious.

The image in Moonwalk One is the

sensuous, light sensitive kind, with deep luminous colours and variegated

texture that we no longer see at the movies. The footage of the rocket launch at

Cape Canaveral is slow and fascinating as the ship penetrates the cobalt blue

sky of the earth’s atmosphere, and moves into outer space. The view outside the

astronauts windows from the space ship as it rotates around the sea-covered

earth, blanketed by whispy clouds, the opticals of the sun, the cold and dead,

but luminous moon, see the image compellingly drift into abstraction. And

as we watch the journey from launchpad to lunar touchdown, perhaps the most

seductive element is the time that is given to this journey. In keeping

with films from the period, the pace of the editing is unhurried, what we might

today see as attenuated, but in reality, is appropriate to a vision of motion

through thousands of miles across what is, effectively, impossible terrain.

|

| Theo Kamecke, Moonwalk One, 1970 |

There’s a real 60s feel to the film:

aesthetically it is very much a product of its time—no digital effects back

then—and no fear of image experimentation, indeed the abstraction that reminds

viewers of the days of psychedelic drugs. Moonwalk

One includes long sequences of audiences around the world anticipating the

landing and watching that great step forward for mankind. And of course, they watch it

on television sets with images so fuzzy and interfered with that we, 45 years

later, will wonder why anyone would bother. But in the late 1960s, audiences

thought that these sometimes barely discernible images were “perfectly clear”

as the guys in Houston confirm to the crew in one radio discussion. As the

American crowds around the country turn skyward to see the long awaited moment,

they have the coolest sunglasses, outfits and cars. The men in mission control

smoke pipes to help them think, use binoculars to see into the distance, and best of all, are the women—regular

seamstresses—who we see making the astronauts suits, by hand, with needle and

thread. All of the footage of the long and detailed preparation for the trip

tells us as much about the culture of late 1960s America as it does about the

technological and human feat of sending men to the moon.

|

| Theo Kamecke, Moonwalk One, 1970 |

What comes out very strongly watching this

film 45 years later is the political exploitation of the trip to the moon. Moonwalk One doesn’t say this, but we

know too well that as Neil Armstrong was placing the American flag on the

powdery surface of the moon, down on earth, battle was being waged against the

Viet Cong. At the end of Moonwalk One,

the narrator asks why “we” celebrated Apollo 11’s trip to the moon with such

verve and passion? He lists a number of possibilities, but the one he forgets

is probably the most convincing: the colonization of space was a great

distraction from the bombings of North Vietnamese base camps in Cambodia,

Stonewall riots and rising tensions on university campuses across the country.

As America’s star was still on the ascent, just before everything went pear

shaped, a very happy and spritely President Nixon is shown in the crowds

gathered to welcome Apollo 11 back to

earth. How could a president who was elected

to end a war, and was in fact doing the very opposite as he escalated the

military attack, win popularity points? Turn the colonization of the galaxy into

an American achievement that warrants the celebration of the century.

No comments:

Post a Comment