|

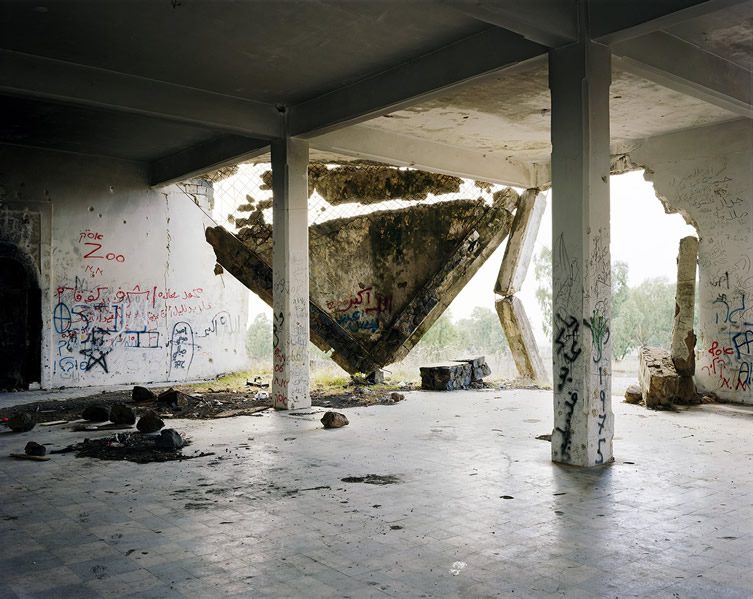

| Thomas Struth, Hushniya, Golan Heights, 2011 |

For my first ever visit to the Folkwang

Museum in Essen, I was treated to a small, provocative exhibition of Thomas

Struth’s photographs from the past few years. Small because unlike the

blockbusters at major museums in the capital cities I usually visit, the

Folkwang has curated 34 images in a themed exhibition. And provocative because

the images together bring new meanings and perspectives to each individual

photograph. Thomas Struth, Nature and

Politics which, had I been charged with titling the exhibition, it would be

called, Industry and Humanity,

presents work that reveals the disastrous results of human constructions that

apparently underwrite social and economic progress. Interestingly, this is only

revealed across the 34, superbly hung, photographs that comprise the

exhibition.

|

| Thomas Struth, Cinema Anaheim, 2013 |

As I wandered around, I felt myself falling

deeper and deeper into human invention and intervention gone wrong. The

photographs show, but do not always represent, the dystopia of a man made

world, either through violations of nature or the mess of technology. The chaos

is communicated through something as simple as the tangled wires of the

Tokamak Asdex near Munich. Even though the machine may be functioning perfectly

well, the representation would suggest the confused and chaotic state of

technology. Even those images in which the represented world is apparently

sterile and orderly--take Cinema, Anaheim, 2013, for example—something is

not quite right. Standing before such an image for a period of time, we start

to wonder what exactly we are looking at. Is that the screen that consumes the

image? And are those steel contraptions on the right supposed to function as

chairs? This is Disneyland afterall, but there is no entertainment in sight.

And then, by the time we reach Curved

Wave Tank, The University of Edinburgh, 2010, the green fumes spewing

toxicity into a contaminated--though clinical--space, we need no convincing of

the destruction of man’s great inventions.

|

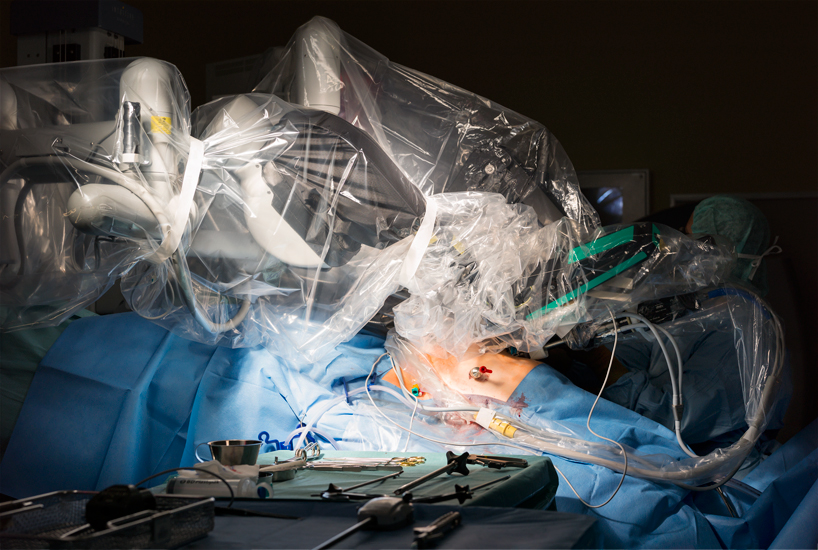

| Thomas Struth, Figure, Charité, Berlin 2012 |

The majority of the photographs give the feeling

abandonment. Machines or experiments built and, having outlived their purpose,

the people have stood up and walked away. The sense of abandonment and decay of

the machines is felt through the absence of humans. Though the presence can be

registered through a glove, or an open computer screen, even a vague figure

dwarfed by the construction, these are worlds in which humans have lost

interest. The museum leaflet refers to the fantasy and desire of industry and

manufacturing as it is represented in the images. If I had to identify where fantasy

and desire is, I would locate it in this sense of abandonment. That is, the

fantasy of creation that ends up as the reality of destruction, unfolds in the

narrative that I impose on the photographs, a narrative that isn’t in the

image.

|

| Thomas Struth, Hot Rolling Mill, ThyssenKrupp Steel, Duisburg, 2010 |

The exhibition also brings together images

of locations that we, as general public , have no access to. This, together

with the unusual angles, the use of distorting lenses and filters, leads us

into places that are strange and unrecognizeable. And when we think we know

them, through photographic manipulation, Struth reveals worlds that are

everything we imagine them not to be. Hot

Rolling Mill, Thyssen Krupp. Steel, Duisburg, 2010 is an example. The

machinery in the image shows everything that Thyssen Krupp, the ambassadors for

the Ruhr region, claim they are not. Here we see the decay, arcane state of

industry, machines rusting over, empty bulwark structures that have the look of

being deserted long ago. The slick and shining steel objects produced by this

machine that feature in the Thyssen Krupp publicity are nowhere to be found in

Struth’s image. When this same photograph was exhibited at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art last year, side by side with museum photographs and other

interiors, the machine was seen as charming and beautiful. Here in Essen, the

same image, juxtaposed with, for example, the inhuman incarceration of the sick

at Charité in Berlin, steps into a

world gone wrong, a nightmare from which there is no way out. The body technologized

by a mass of wires and machines in Charité

shows the danger and horror of technology and industry, and there is nothing

enchanting about it. Of course, our shock before this image carries over to our

perspective of the Thyssen Krupp machinery. And then, around the corner, an

image of the Golan Heights shows a roof collapsed, a world falling apart,

extends the nightmare to its most obvious conclusion. Even though there is not

a trace of technology or industry in Hushniya,

Golan Heights, 2011, we know very well how this happened. The frightening

narrative of human invention reaches its most terrifying moment in this images

that shows none of the inventions.

No comments:

Post a Comment