|

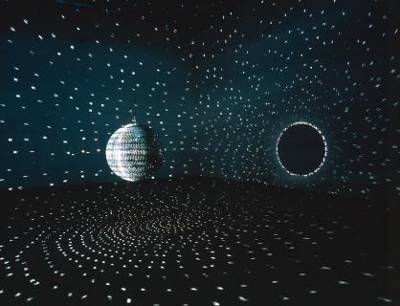

| Mischa Kuball, Space Speech Speed, 1998/2001 |

Unna, a sleepy town in North East NRW has

one attraction that makes the effort to get there worthwhile: the Centre for

International Light Art housed in an old brewery. The exhibition spaces are

built into the underground storage, cooling and change rooms, that is, spaces

otherwise cloaked in complete darkness. It is, apparently, the only museum of

its kind, devoted solely to light installations. This makes it a big drawcard,

and though I enjoyed the visit, I was slightly disappointed. More on that

later, first, what’s most impressive is the array of international artists’ whose

work is exhibited here. There's no Dan Flavin, Bruce Nauman Anthony McCall or Robert Irwin, but many major contemporary international light artists have at least one piece on display in

the bowels of the unrenovated Linden Brewery.

|

| Olafur Eliasson, Der Reflektierende Korridor, 2002 |

Built for the working brewery 120 years

ago, no one space is the same as the next, and no space seems to have a natural

or logical connection to the next. Accordingly, each art work, exploits this

isolation and is contained by its space. Thus, the experience is one of going

from room to room, where corridors and transition spaces constitute discrete and

often unusual spaces. This is all to say, the experience is not one of wandering

through the light installations, but more a series of unrelated immersions in light.

Most impressive are those works that engage with the architecture of the building.

In one of the most extraordinary works, Olafur Eliasson has us walk across a

grated bridge between what at first appears to be a curtain of sparkling light

on either side. And then, as we step close to the curtain, our feet get wet.

The beads of light are created through spot lights above shining on drops of

water as they cascade into the pool beneath the grated bridge. The confusion of

what we are seeing, hearing, touching, even smelling, is the most outstanding

example of the lesson taught by a number of these sculptural installations.

Visual perception is only the first of the multi-dimensions of light art.

|

| Keith Sonnier, Tunnel of Tears for Unna, 2002 |

Some of the works are confronting, again in

ways that surprise. Keith Sonnier’s Tunnel

of Tears for Unna installed in a storage space, for example, turns the

rough hewn walls, lined with pipes, switches, butts and other paraphernalia

into red and blue tunnels. Sonnier plays with the familiar visual effects of

opposite colours, so when we are in the space bathed in red through murano

glass fluorescent tubes, we look back at a white lighted space and it appears

green. And then when we move to the blue room beyond the red one, the white

becomes yellow. Most surprising of all is the warmth we experience over time

standing in the blue light, and then when we move back to the red, it is harsh,

cold, alienating. This is the surprise of Sonnier’s tears: blue and red are

supposed to create cold and hot respectively, not the other way around. From

Sonnier we also learn that light is an emotional experience. The confrontation

of the harsh red light is so unexpected. Furthermore, we are reminded through

this confrontation that the seeing is just the beginning of our experience of

light.

|

| James Turrell, Third Space, 2009 |

|

| James Turrell, Third Space, 2009 |

Light art, like the stuff itself, comes in

many different media or types of light. The exhibition includes a lot of neon,

as the chosen material of the -post-Nauman generation of light artists, but

there is also a very special natural light art work using the sky over Unna by

James Turrell. Turrell has made a camera obscura in the only above ground

installation. It’s a simple circle cut in the ceiling of a purpose built room

(not part of the original brewery) through which day or night light falls onto

a circular marble slab inside. Turrell place lenses in the circular opening,

and thus, when inside the room, we look down at the sky as it moves across the

opening above. Thus, it is not only the image that is inverted through

Turrell’s camera obscura but logic too: we look down to see what is above us.

In addition, the clouds in the sky seem to race across the opening, a striking

antithesis of their apparent stillness when we stand below and look at them above

us. Having spent the last two hours in the catacomb-like spaces below ground,

immersed in neon and artificially created spaces, coming above ground to be in

the midst of Turrell’s creation, I was amazed by the fact that, all along,

nature gives us, afterall, the most surprising art work.

|

| Francois Morellet, No End Neon (Pier and Ocean), 2001 |

There are many other works - by Joseph

Kosuth, François Morellet, Christian Boltanski, Rebecca Horn and Mischa Kuball

among others. As we go through the spaces, we are given new perspectives on space,

on our body, on the relations between art and nature, above and below ground,

all of which we experience through our own movement and senses. My one

disappointment in the exhibition was that, even through a large number of works

intelligently engage the spaces they occupy, none of them engage the history of

the production processes or the work and activities that once took place in the

Brewery or its spaces. This, in itself, is not a criticism. However,

considering the tendency of public artworks, even those in museums, to engage the

history of the region’s past in the Ruhrgebiet, it would have been interesting

to see light works engage on this level. Energy, water, light are all key to

the industrial production that gives the region its identity, and I would have

thought it’s acknowledgment would make this museum more than just the only one

devoted solely to light art. Otherwise, once down in the storage spaces of the

Linden Brewery, we could be anywhere in the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment