|

In Paris I am always curious to know what criteria

have been satisfied to earn an exhibition at one of the state museums. Why

would the French be interested in the censored and banned images from modern

Iran? The mystery is solved very shortly after entering Unedited History, as we learn that so many Iranian artists from the

post-1979 Revolution period came to France, and have indeed made their name

here. At least, a large number of those exhibited are now living and working in

France.

|

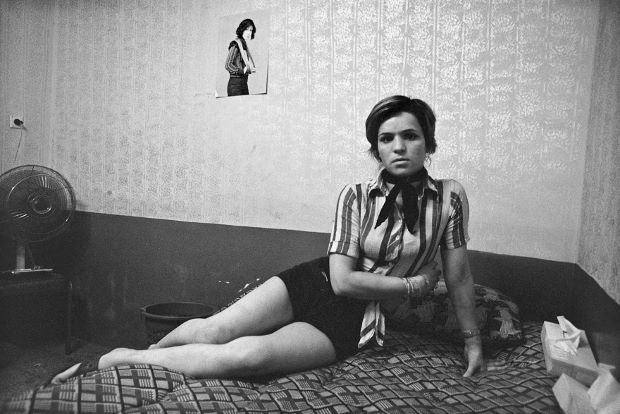

| Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975-1977 Documentation accompanying exhibition |

Unedited

History starts tentatively with the paintings and

other arts of the pre-Revolutionary Shah’s Iran. I say tentatively because the works

were preoccupied with aesthetic issues, experimenting with form and style in a

search that brought together traditional and Western art forms. And then the

revolution happened. By the late-1970s, all the experimentation of the previous

two decades was left by the wayside, overwhelmed by an urgent and unprecedented

passion for change and the possibility of freedom in life and art. Among the

treasures on exhibition in Unedited

History was footage shot by Kamran Shirdel of the 1979 revolution as it

took place around him. Entitled here Memories

of Destruction: Rushes from the Revolution, we see, minute by minute, the

slow unfolding of events that changed the world. Two things struck me about

this rare footage: first, much of what we see is a dense crowd, walking. Motion

and protesting in Iran 1979 belong together. I don’t know what to make of it,

but I think of, for example, the Egyptian Revolution, and I think of Tahrir

Square packed to the rafters with protesters sitting, standing, protesting. And

I wondered why the walking in Iran? Was this related to the relative invisibility

of the Ayatollah in the leadup to the overthrow of the Shah? That is, with no

leader to look at physically, the people were left to walk in search of

freedom? Second, I was struck by the separation of men and women in the

footage. Of course, they were separated, even in revolution, but nevertheless,

it’s a surprise to see the adherence to religion in the midst of revolution.

Even when this revolution is in the name of Islamic Law. In confirmation of

what I suspected was Shirdel’s extremely rare footage, a google search turned

up no reference to the film. Just to see this footage is reason enough to go visit

this exhibition.

|

| Kaveh Golestan, Citadel, 1975-1977 |

Also really powerful were Kaveh Golestan’s

photographs taken in the redlight district of Shahr-e No, otherwise known as

the Citadel, in Tehran, 1975-77. The area was erased in the 1979 revolution, and

again, I found myself amazed at the awkwardness of gender relations. It wasn’t

just the presence of prostitutes in the Muslim-Arab world, but the presence of

the male photographer inside that world that left me amazed by the images. And

it was a sparse, sad, cold world. Often with a single image on the wall, a threadbare

cover on the bed or its equivalent, years of grime on the walls, there’s

nothing glorified about sex in these photographs.

|

| Tahmineh Monzavi, Ateliers de Confection de Robes de Mariée Quartier de Mokhberodeleh, Teheran, 2007-2011 |

|

| Narmine Sadeg, Office of Investigation into Diverted Trajectories, 2014 |

|

| Chohreh Feydjou exhibition view Unedited history: Iran 1960-2014 |

In the final rooms, the powerful work of Chohreh Feyzdjou and Narmine Sadeg bring the

concerns of Iran, its devastated history, and the same but different

melancholia we saw in the photographs, to the West. Both artists digress from

the documentary photographic and filmic form that became the chosen media for

the representation of revolutionary and post-revolutionary Iranian life and

politics. Their deeply sensual and tactile sculptures exude the pain and death

and dislocation of being in exile, coming from a country that has suffered

everything. Feyzdjou’s boxes, cabinets, racks and shelves filled with decaying,

burnt and wasted objects, all meticulously labelled, remind us of the

impossibility of holding onto anything. And through the archival collection and

cataloguing of now useless objects, bottles and papers, we are left in no doubt

as to the futility of trying to retain what will always disappear.