|

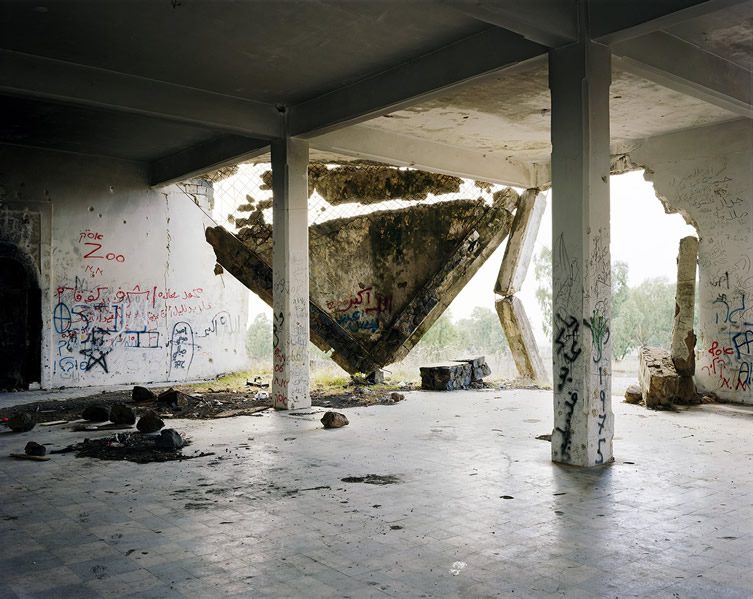

| Inside the Glaskasten Museum, Marl |

In Bottrop and Marl, cities that are almost at the end of the world, North Rhine Westphalia boasts two of its most exquisite museums. Bottrop and Marl are not high on the tourist list, though they should be. Before stepping inside the Josef Albers Quadrat Museum in Bottrop and the Glaskaten Museum in Marl, I was overcome by a feeling of peace and serenity, as though I had stepped into oases of perfection in the

middle of these former industrial hinterlands. Both museums are encircled by sculpture gardens filled with works behaving like totems imploring our contemplation, engagement and conversation. As I wandered through the two sculpture parks I couldn’t help thinking that the Ruhrgebiet does sculpture like Italy does Renaissance painting. In the same way that a Masaccio or a del Sarto change color and meaning as the sun moves across the sky on the walls of their Florentine chapels, outdoor sculpture in these Ruhr museums convinces me that I can never see it in a white cube again. In fact, their exhibition by these museums is so convincing that the placement of sculpture in the natural environment feels like a return to where it belongs. The magical transience of the day, the changes in light, in the weather, the mood of the trees, give the sculpture a narrative that sweeps both art and viewer into an ethereal other world. The elegant and poignant structures in steel and concrete enter into conversation with the trees, the wind, the rain and the birds that give them a community, making a mockery of the apparent intransigence and rationalization for which their materials are better known.

The sadness and melancholy

of Alf Lechner’s 3/72 Rahmenkonstruktion (1972),

four steel cubes on a hill in the park, in the fading light of the long

Northern European summer night, the glinting playfulness of Naturmachine, 1969, finding use as a

playground for children, the game of Richard Serra's Untitled, 1972 two steel blocks, one balancing precariously on top of the

other on the Rathaus plaza in Marl, all of them convince us they are alive,

personified, performing for us. In Bottrop, I sat in the garden and watched a

bird cleaning itself, displeased when I sneezed and disturbed its solitude. Max

Bill’s Einheit aus Drei Gleichen Volumen 1979

looked on from the opposite side of the pond in which the bird stood on a rock

among waterlilies. Donald Judd’s Bottrop-Piece

(1977) changes shape and color, and the appearance of its material from stone

to steel depending on where we stand to view it. At a distance it could be

concrete, up close it is the same corten steel out of which so much of the work

in the Ruhrgebiet is made.

The indoor spaces of both

museums are likewise superbly curated - in Bottrop, room upon room of Josef

Albers' color experiments. Homage to the

Square in green and gray, orange and red, blue and purple. The Quadrat

museum is a veritable retreat cut off from the rest of the world. It seems

impossible that Albers’ silent and delicate paintings in what feels like sacred gray rooms could

be conceived in the same breath, in the

same century, as the coking plant 10km down the road. And in Marl, the collection

belongs to the town, paid for with taxes charged to the employees of the

one time prosperous mines. The richness of the collection is a reflection of

the success of mining and industry in the once wealthy town. The

Glaskasten sculpture museum is literally that, two layers of glass constructed

around a former thoroughfare. The outside rim offers something like a

pleasantly confusing disorientation between inside and outside. Walking

across the original rough-hewn floor, the same surface as the plaza outside, is like a no man's land in which to be restored. A poignant

work, Danzatore, 1954, by Marino

Marini sees a woman look up and out through the windows to the sky, facing the

plaza, imploring passers by to connect with her. When I stumbled upon Hermann

Breucker’s Die Trauernde, a woman in

mourning, her face hidden in her hands, in the former cemetery that has become an extension of the sculpture park, I thought Marini’s dancer must have

been reaching out to her suffering sister.

One of my favourite pieces in Marl was a shipping container with video images for windows, placed in the

thoroughfare outside the glass box; it forms an obstruction to the world

passing by. Anna Schuster’s Continued

Landscape 1997, shows images of a passing landscape seen from a train

window: we look inside a box at windows that provide a view of an outside where

we cannot be. The multiple perspectives of images in motion in a shipping

container left to rust outside a museum, is confusing. I thought the piece was

like a summary of all the sculptures, like the museum with its unique

architecture is an expression of what lies beyond it. Everywhere across the Ruhrtal is an ever-transforming

landscape, being looked at and looked from, unlikely perspectives, confronting

and changing our view of a world in which the opposite always holds true.

|

| Tetraeder, Bottrop |

Though I

didn't do this because I was too confused by the train connections, I suspect

that a visit to Marl should be completed by a tour of the local Chemical

Industry which includes a panoramic view over the Ruhrgebiet. Climbing up a tower to

gain a strange re-orientation of a world whose identity was for so many years

governed by what was below ground, invisible to the eyes of people like me.

Likewise, in the environs of Bottrop, the Tetraeder is a must. On the top

of a slag heap, this steel construction demands so much from us: to look up and

at, to look down from, to climb, stand still and let go to a landscape

infinitely more filled with secrets than we can ever imagine. The command of

the wealth of sculptures in the two museum parks speaks to the industrial and

post-industrial landscapes, confronting us with their ephemerality, their

transience and reflection back on a natural world that will continue to change,

well beyond the immense structural redefinitions that motivate the region’s

identity today.